Experimental Overview

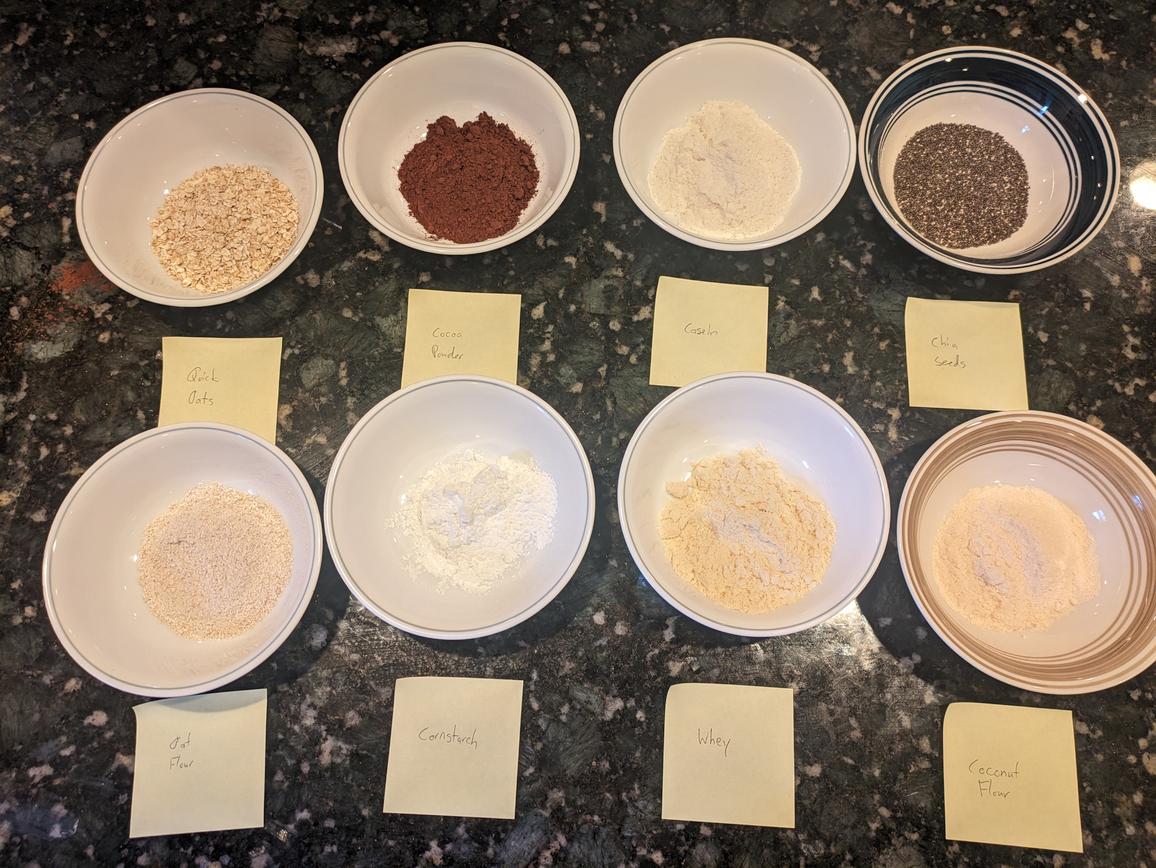

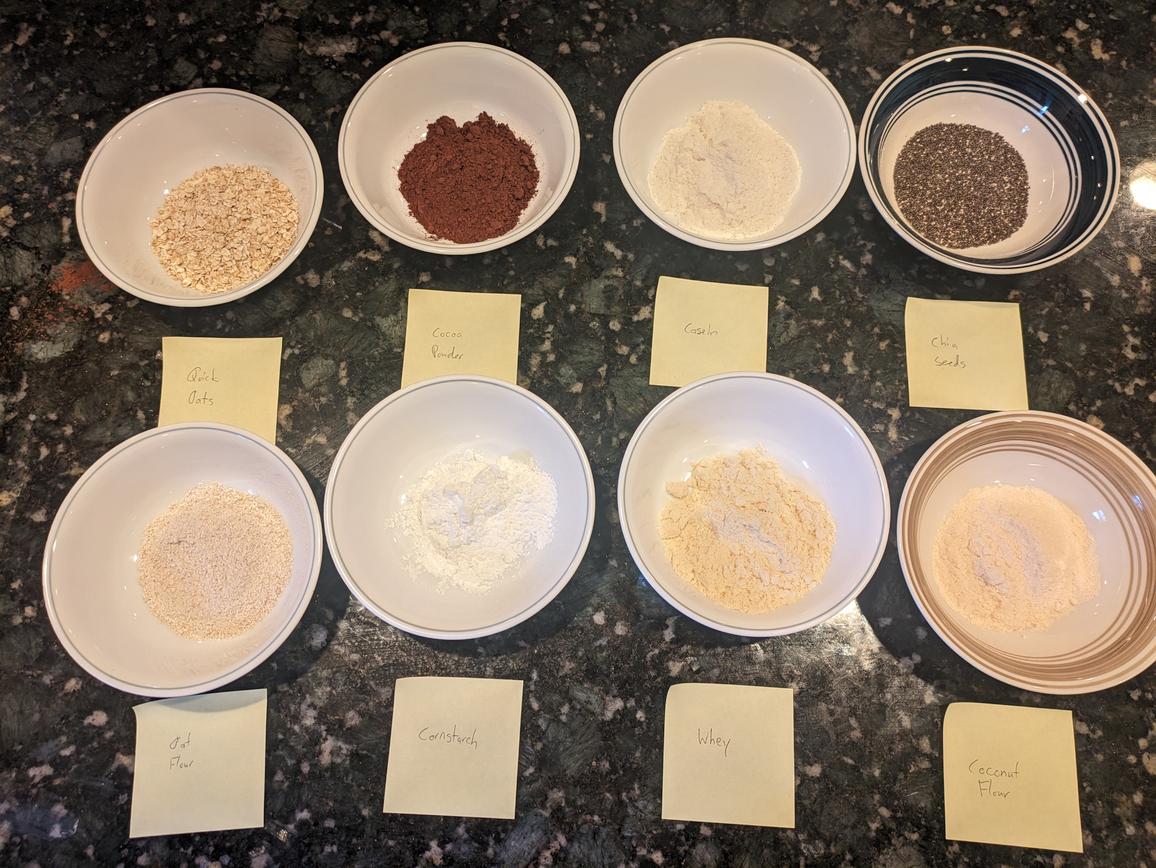

In making recipes, it's helpful to know when you can substitute one kind of flour for another, and what effects it will have on your finished good. Here, I'll be taking 30 g, or about 1/4 cup (volume may vary) of each flour, and mixing it with a variable amount of water until I have a cookie dough like consistency, and letting it chill in the fridge for an hour. I want something that is not too dry and not too sticky, and that holds its shape and can be formed. Each of the flours will absorb water differently, so if you are swapping one for another in a no bake recipe, this will be a helpful page for you.

List of Flours Tested

1. White Flour

a. Not Heat Treated

b. Heat Treated

2. Whole Wheat Flour

a. Not Heat Treated

b. Heat Treated

3. Vital Wheat Gluten

a. Not Heat Treated

b. Heat Treated

4. Oatmeal

a. Oat Flour

b. Quick Oats

5. Cornstarch

6. Cocoa Powder

7. Protein Powder

a. Whey Protein Powder

b. Casein Protein Powder

8. Coconut Flour

9. Chia Seeds

10. Peanut Flour

11. Flaxmeal

12. Almonds

a. Almond Flour

b. Almond Meal

13. Millet Flour

14. Hemp Seeds

15. Psyllium Husks

16. Ground Coffee

17. Granulated Sugar

Note About Heat Treating

As you may or may not know, wheat based flours cannot be consumed raw due to the risk of E. Coli. Heat treating the flour typically involves cooking it in the oven, microwave, or on the stove until it reaches a temperature of 160F, where all the bacteria would be killed off. The flour then can be enjoyed in a raw dessert, such as edible cookie dough.

As for the testing, I'll be baking a tray of the flour at 300F for about 10 minutes, or until lightly browned and an instant thermometer reads 160F. Note that I'll be using weighing out 30 g each of the heat treated flours post heat treatment, not before.

Testing

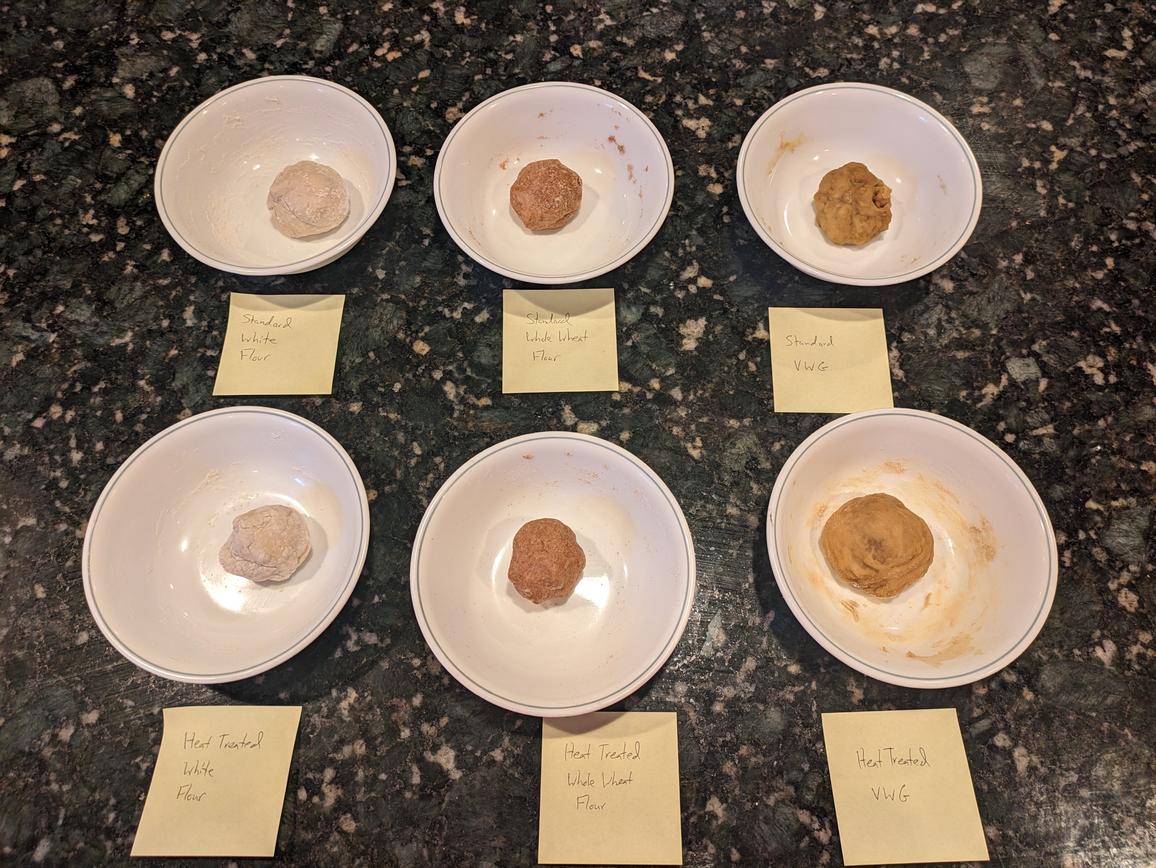

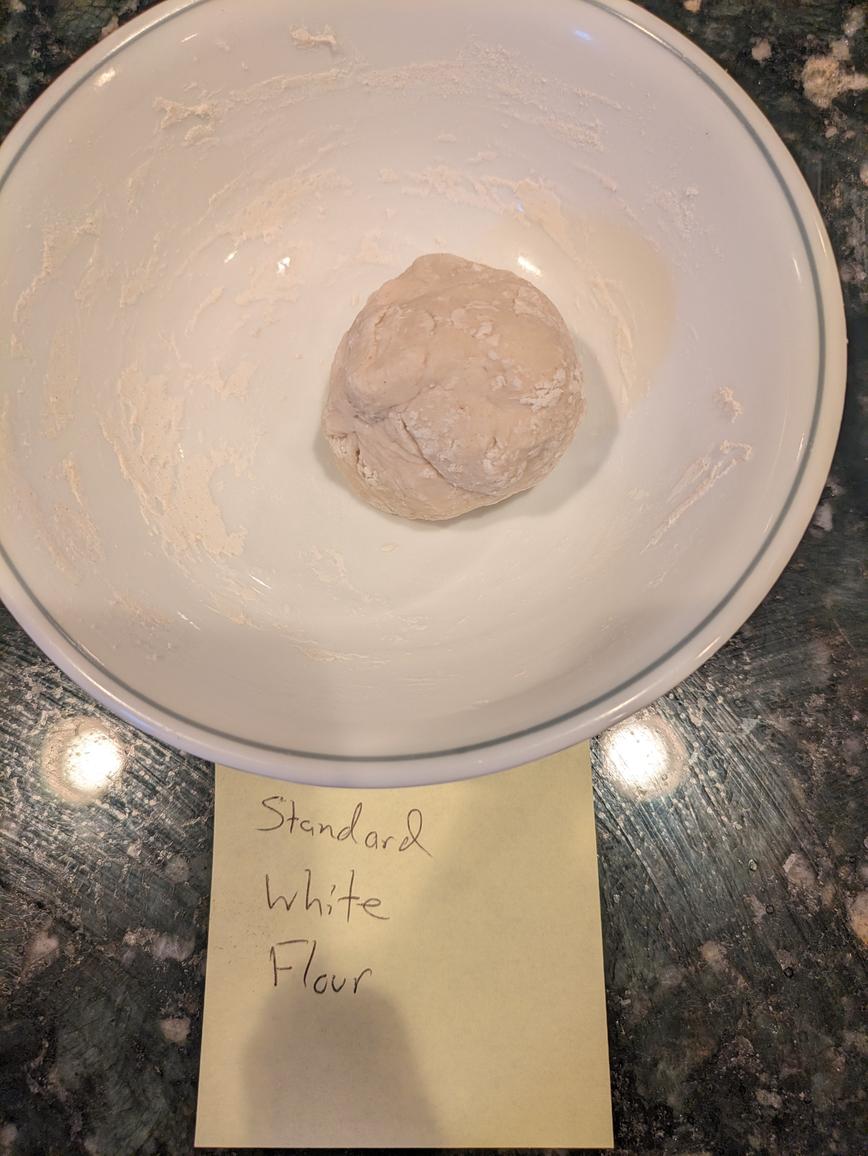

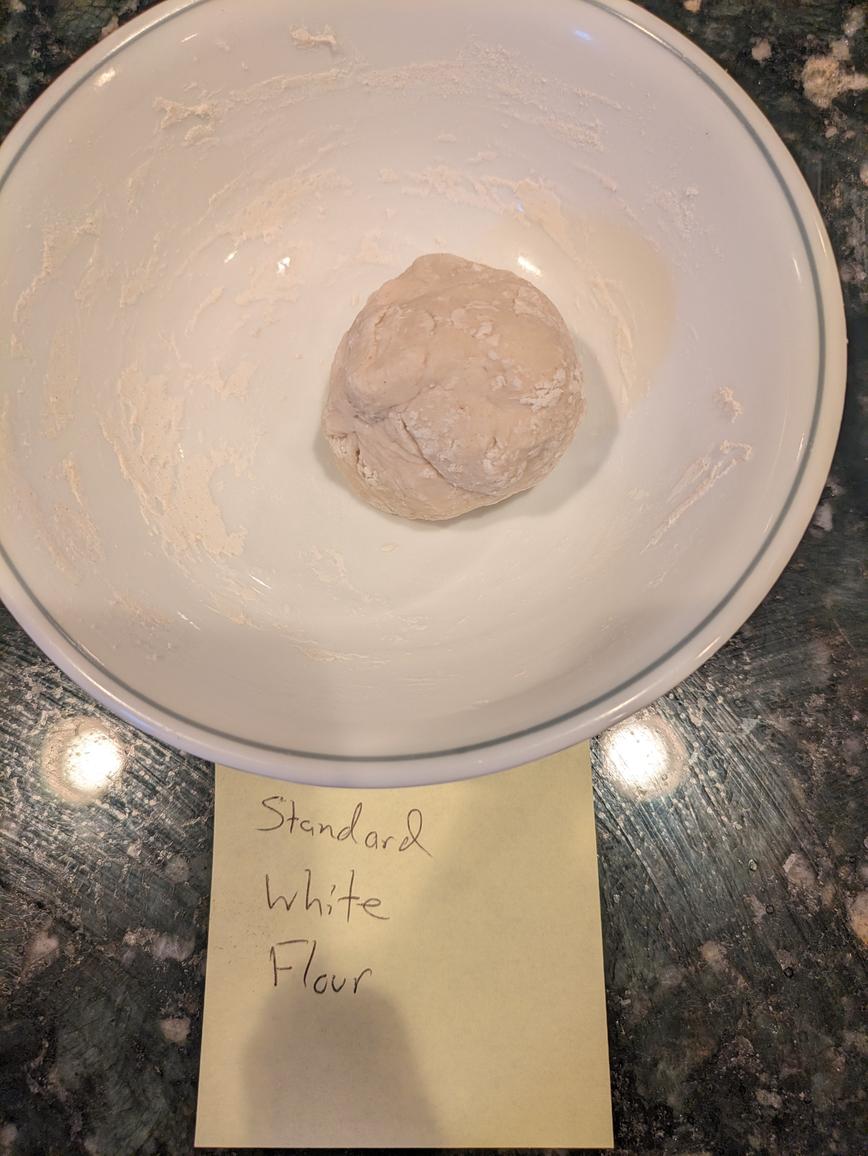

1a. White Flour (Not Heat Treated)

White flour, or all purpose flour, is the original flour. It's probably the one you're most likely to have in your kitchen. I avoid using it in recipes, as its highly processed, bleached, and low in nutrients.

It serves as a good basis though if you'd like to swap white flour for a more nutritious option. Here, I'm using a general store brand bag of white flour.

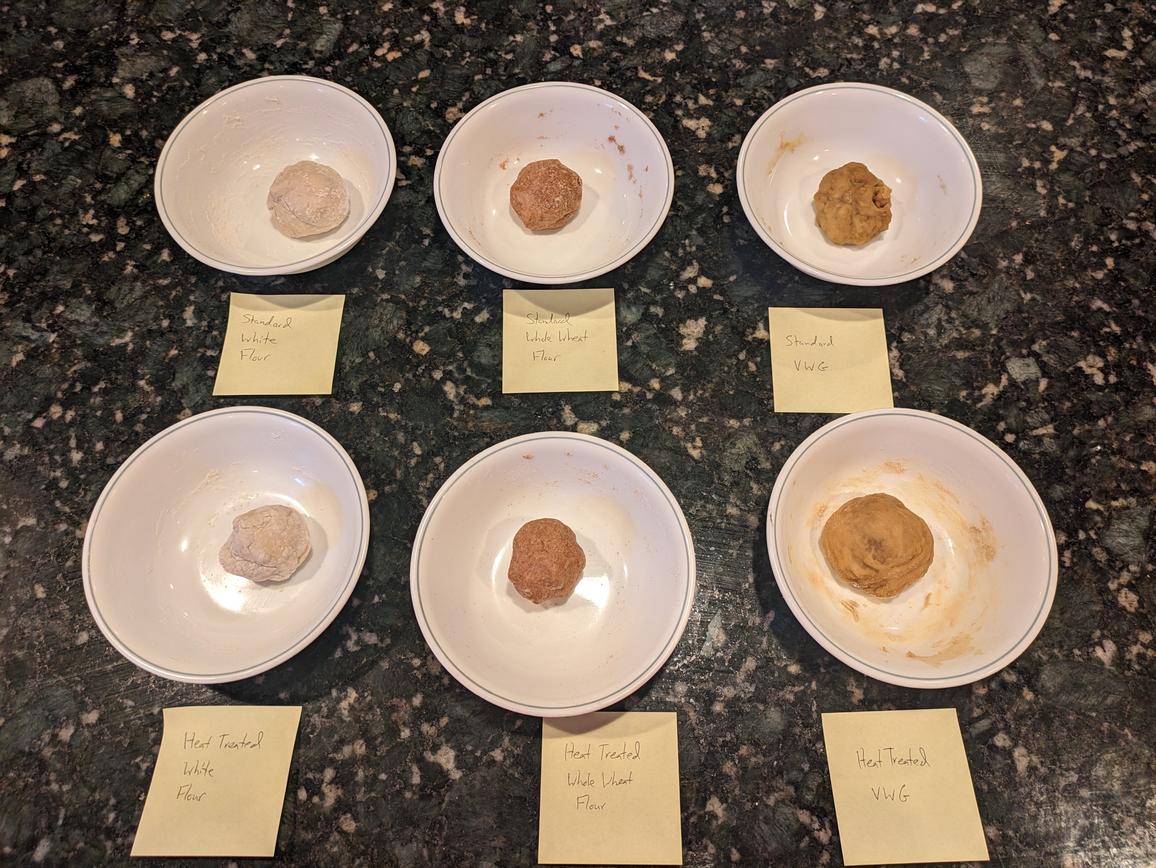

Right away, I've realized that the wheat based flours will be the most difficult and least accurate. They stick more, and their doughs will more closely represent bread dough than cookie dough. For the standard white flour though, I found that 17 g was enough to bind 30 g all purpose flour.

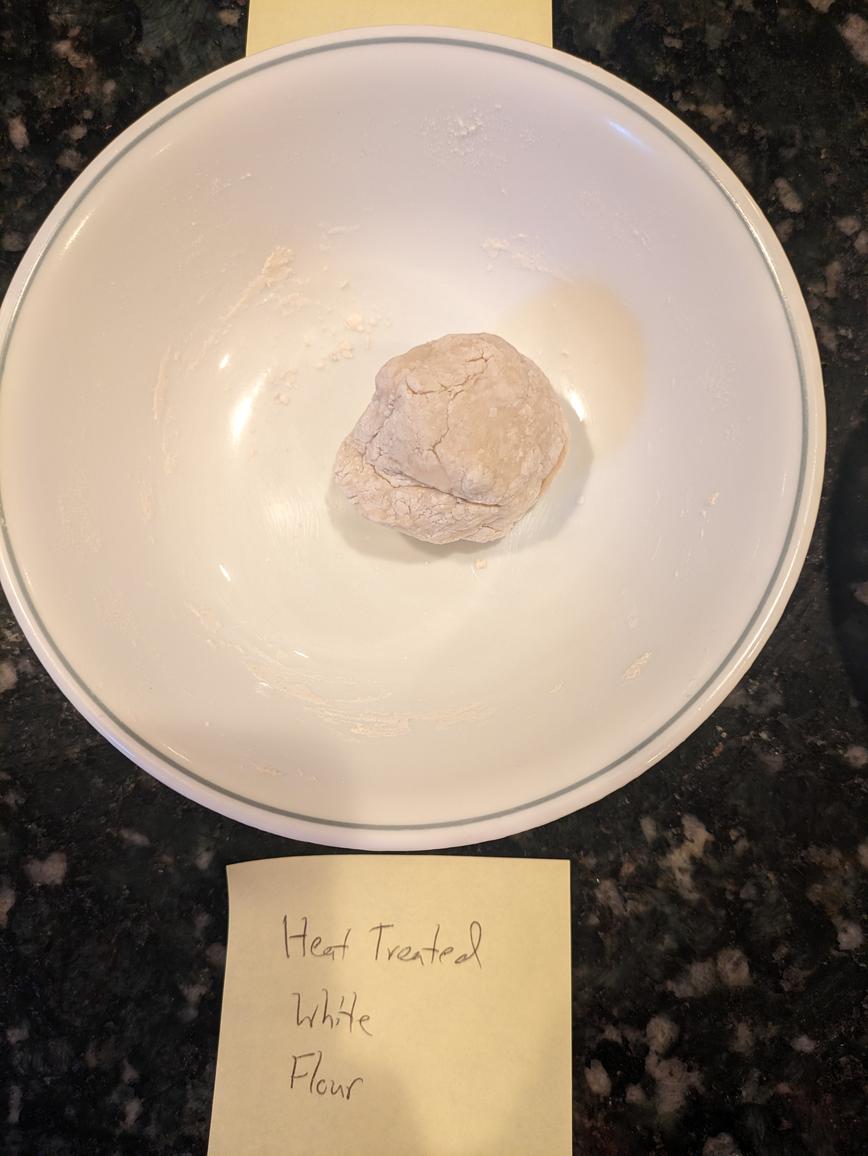

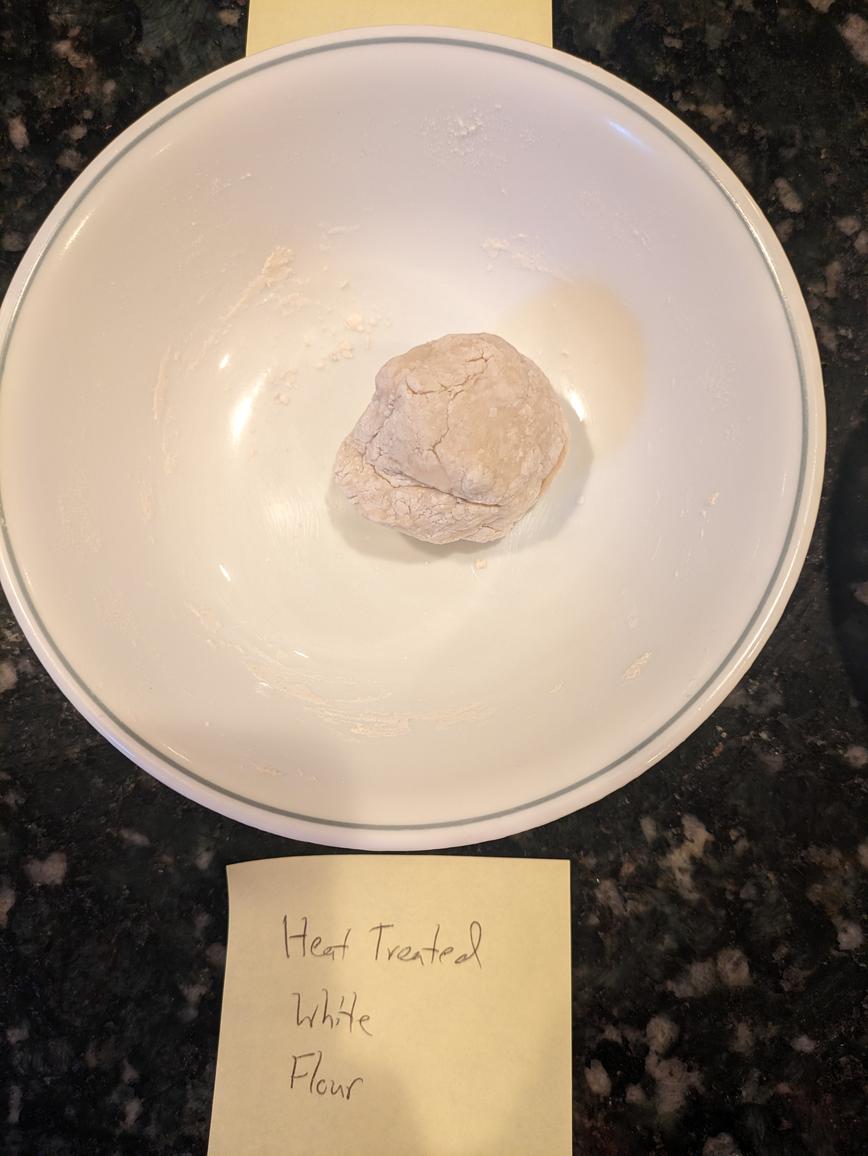

1b. White Flour (Heat Treated)

I wanted to see if heat treating the flour would lead to any difference in the amount of water absorbed by the flour. As it's parially baked, some of the water would have cooked off, leaving a dryer flour able to absorb a little more water.

Turns out, 30 g of heat treated white flour was able to absorb about 20 g of water, which is a 16.2% increase. It's hard to tell if this is a significant difference, or just due to user error. Based on my hypothesis above though, it would seem that some of the water cooked out of the flour, allowing the heat treated version to take in more.

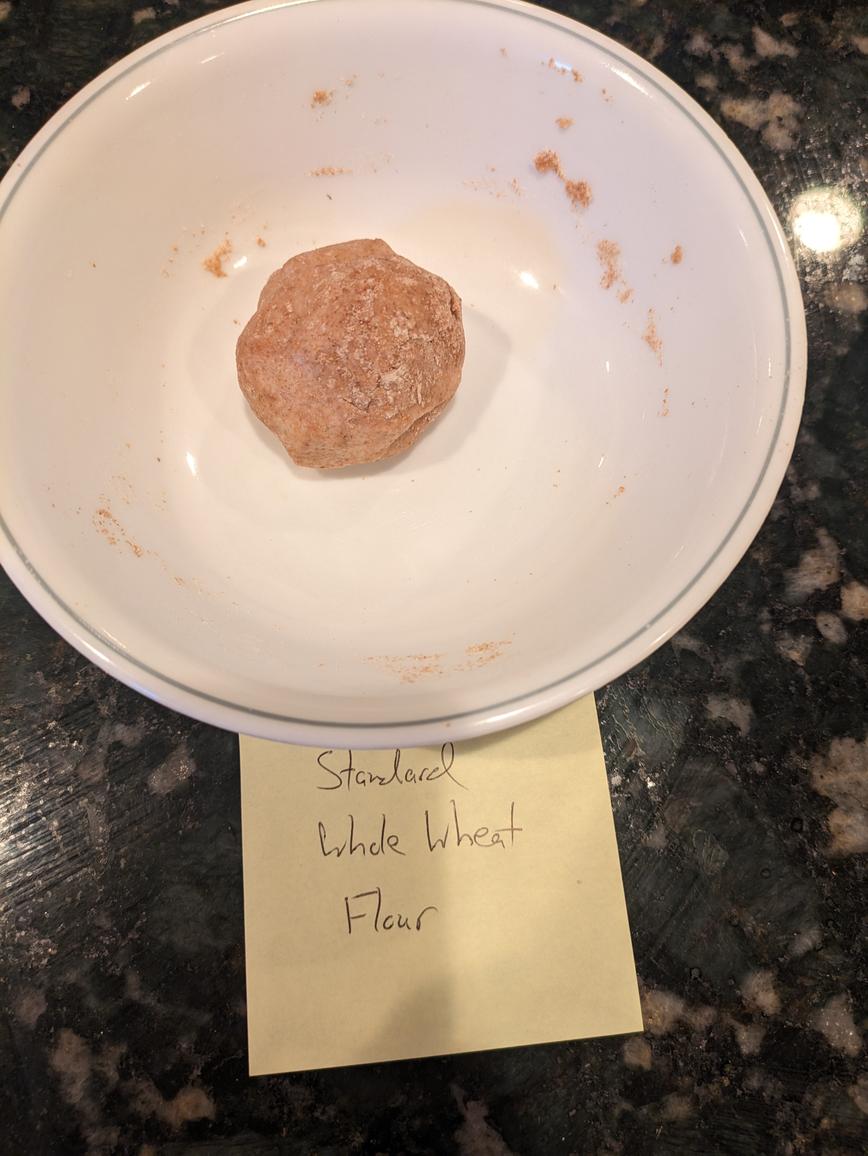

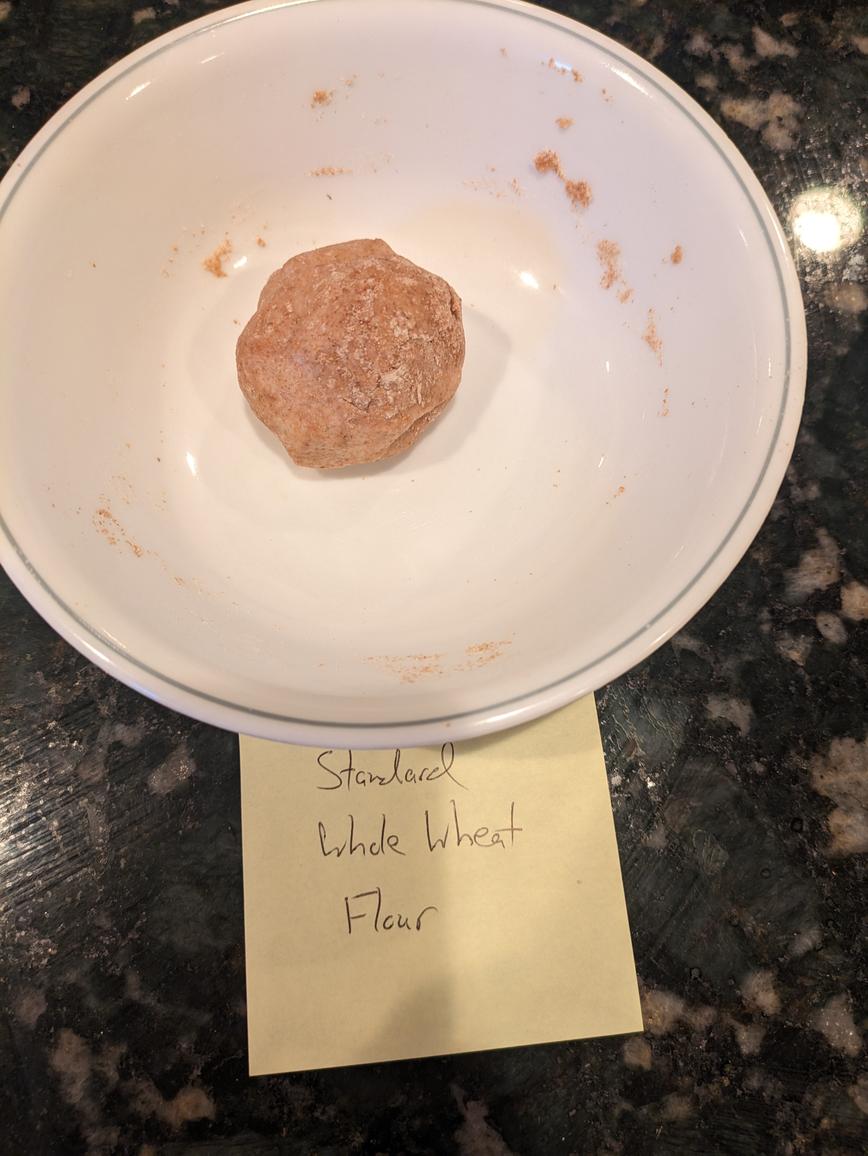

2a. Whole Wheat Flour (Not Heat Treated)

Whole wheat flour is a healthier option as compared to white flour. It is flour of the entire wheat kernel, leading to more protein, fiber, and micronutrients.

In making loaves of bread, I used to use about 320 g of water for 500 g all purpose flour. Now, when I make whole wheat bread, I use about 360 g of water for 500 g whole wheat flour. Therefore, I would assume that the whole wheat will take in more water. The brand of flour I'm using is King Arthur.

It took 22 g of water for 30 g of whole wheat flour, which is a 25.6% increase over the standard all purpose flour experiment. This would suggest that when substituting white for whole wheat flour, you should either use a little more liquid, or start with less flour and go based on the feel of the dough to see if you need to add more.

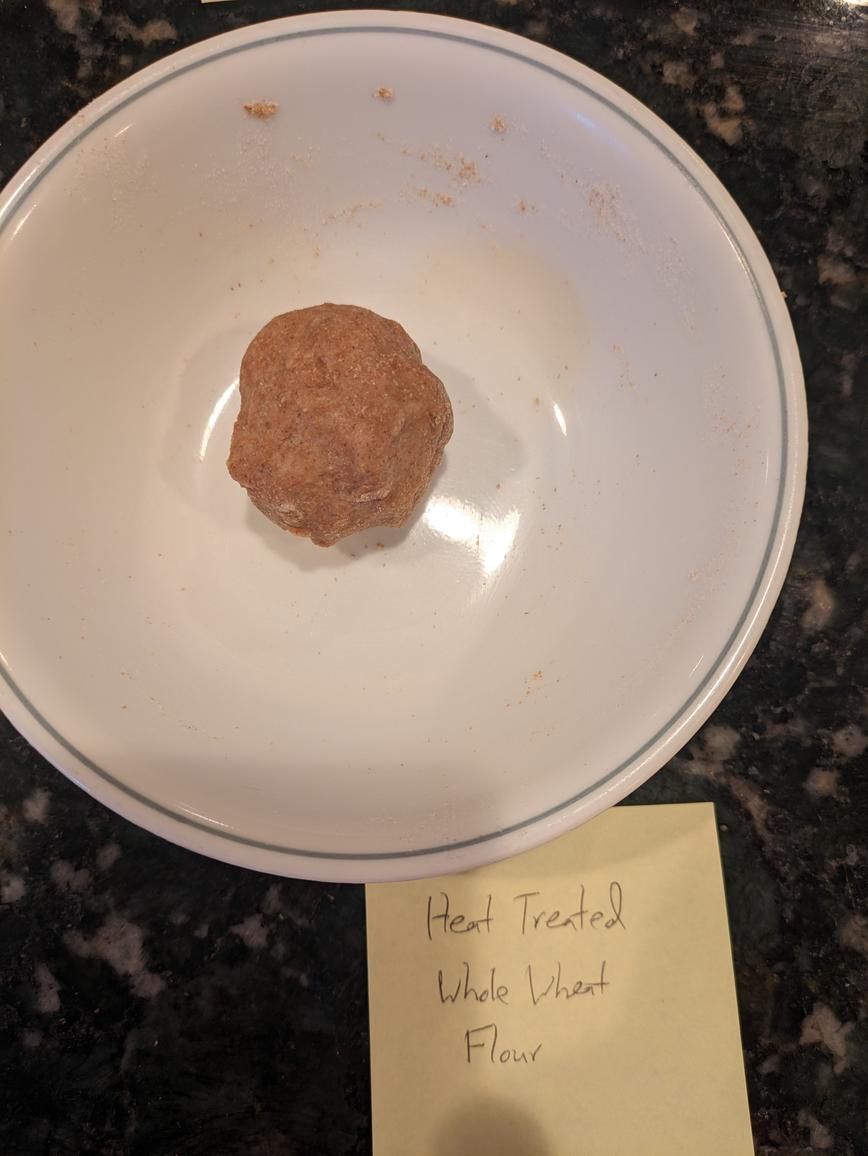

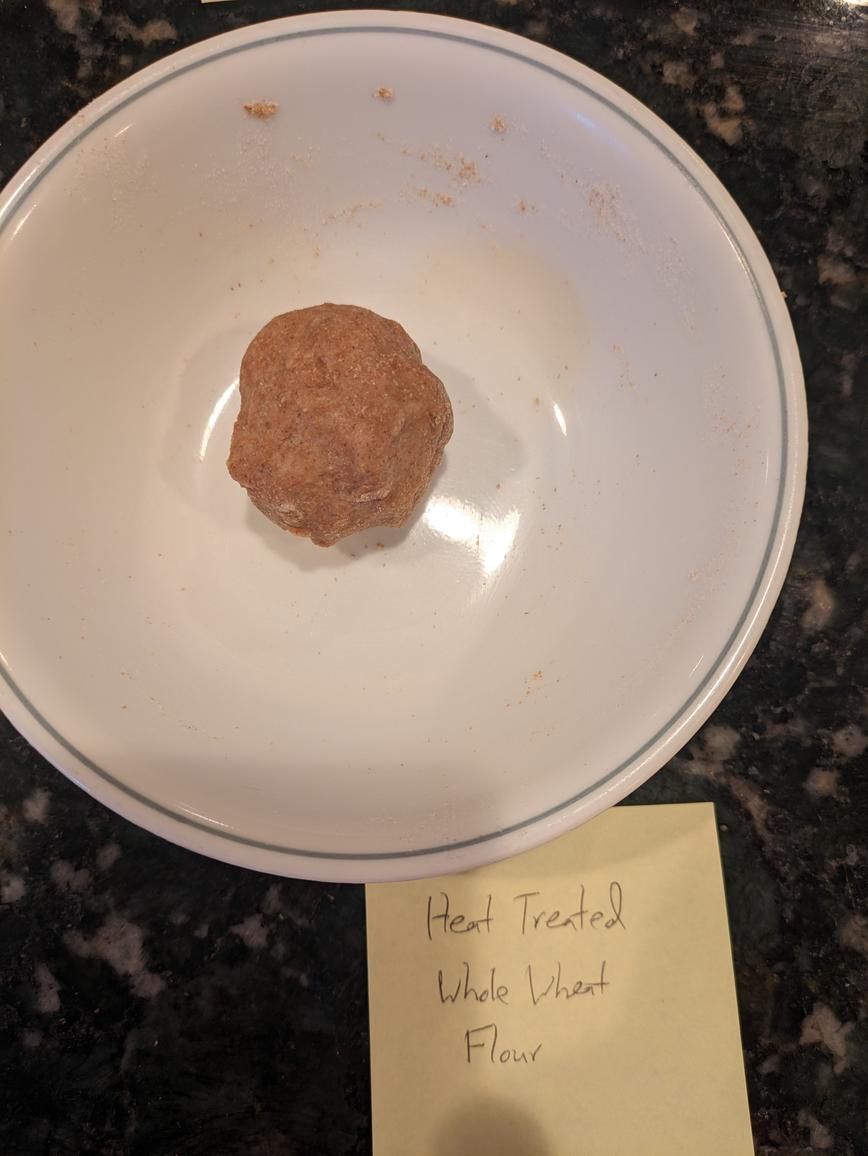

2b. Whole Wheat Flour (Heat Treated)

Again, just like with white flour, whole wheat flour cannot be consumed raw, due to risk of E. Coli. I wanted to again test if heat treating will make a difference from the trial above.

As expected, the heat treated whole wheat flour absorbed a little more liquid compared to the regular whole wheat flour - 23 g of water for the 30 g of flour, as compared to 22 g. While this is slightly more, my guess is that is not statistically signficant, and would be chalked up to any user bias or error. Heat treated whole wheat flour may absorb slightly more water, but a larger sample would be needed to know for sure.

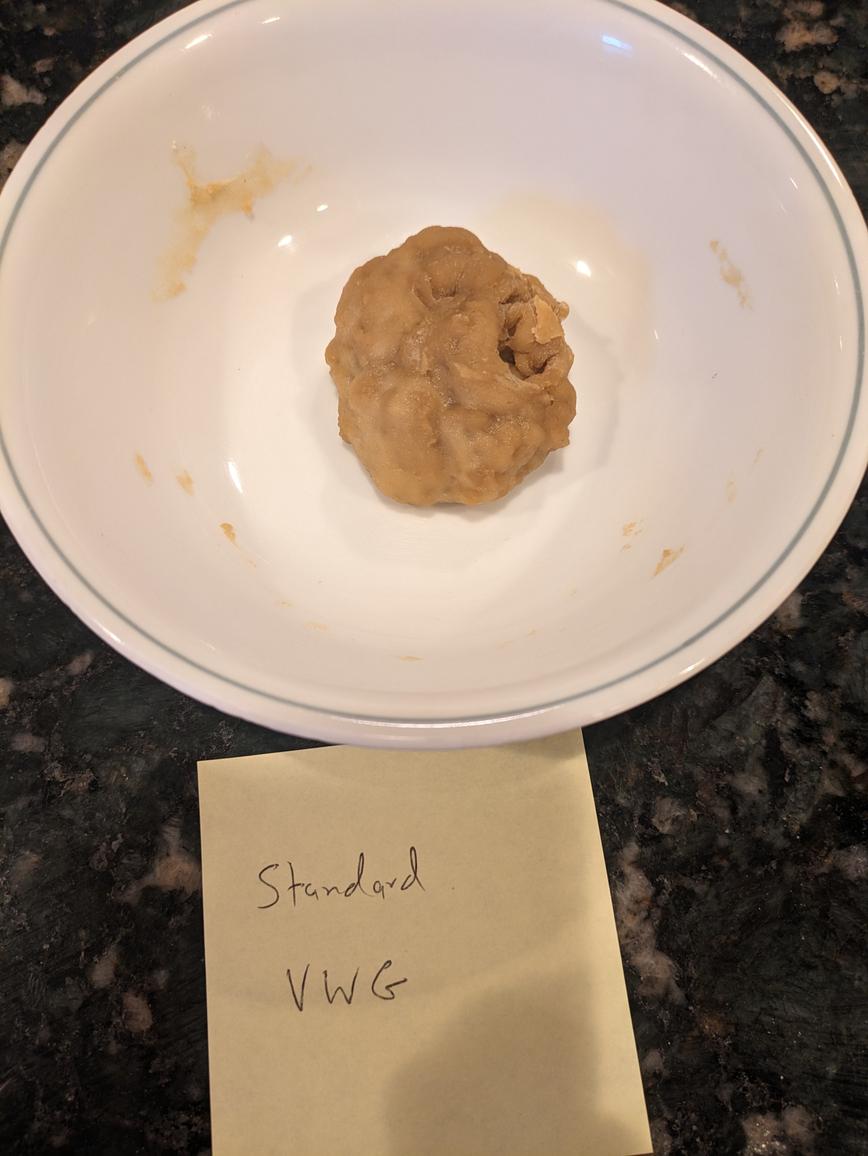

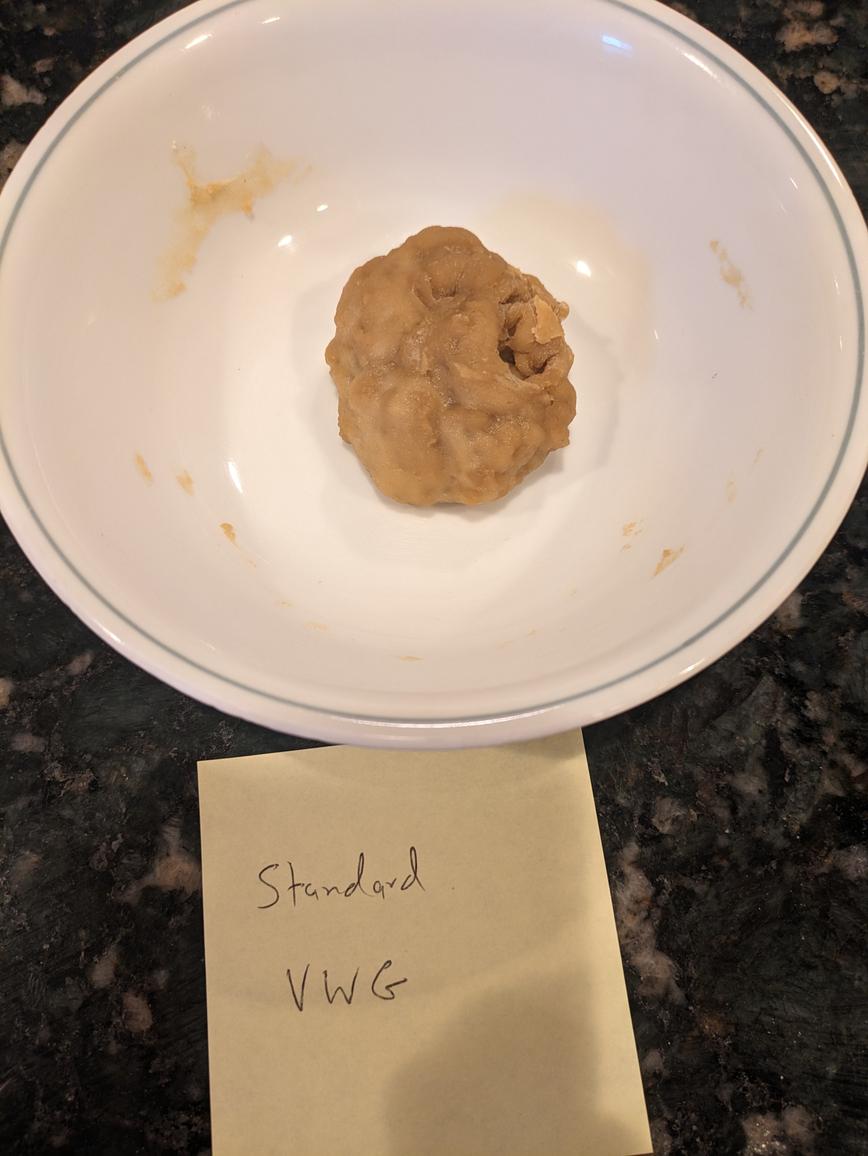

3a. Vital Wheat Gluten (Not Heat Treated)

Vital Wheat Gluten is the anti-Celiac flour; it's entirely gluten. It's low in carbs and high in protein (remember gluten is a protein). I typically add a little bit into my whole wheat bread loves, as whole wheat flour contains less gluten than white flour, so it has a harder time rising and can become dense without a little extra gluten.

I'm predicting that not only will this not need very much water, but that it won't really come together at all, and would be very stringy and tough. Gluten is what gives bread structure, but too much would be gummy and gross (my prediction, let's see how it turns out).

Surprisingly, the VWG was able to hold together into a dough without being too difficult to combine. The 30 g of vital wheat gluten needed about 25 g of water, which is a little more than even the whole wheat flour. Note that biting into this is like chewing on rubber; I would not recommend a 1:1 swap of any flour to vital wheat gluten pretty much anywhere.

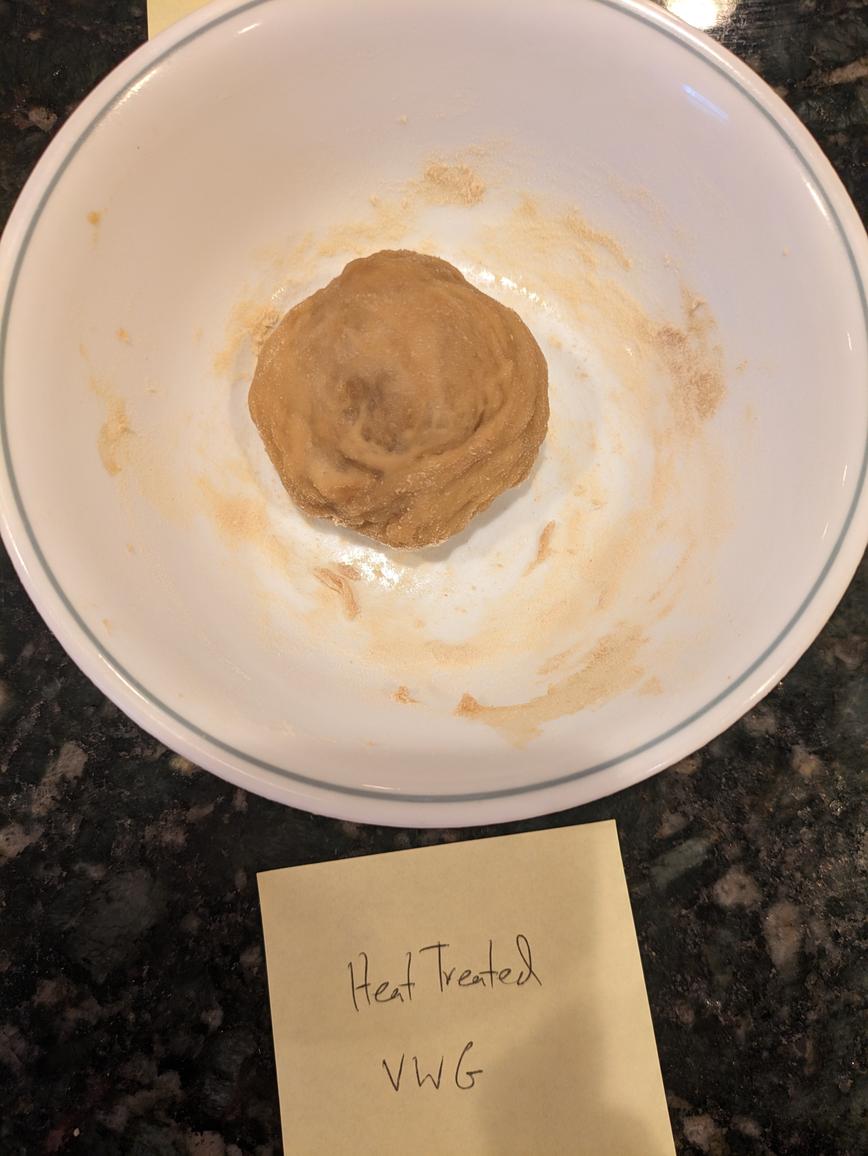

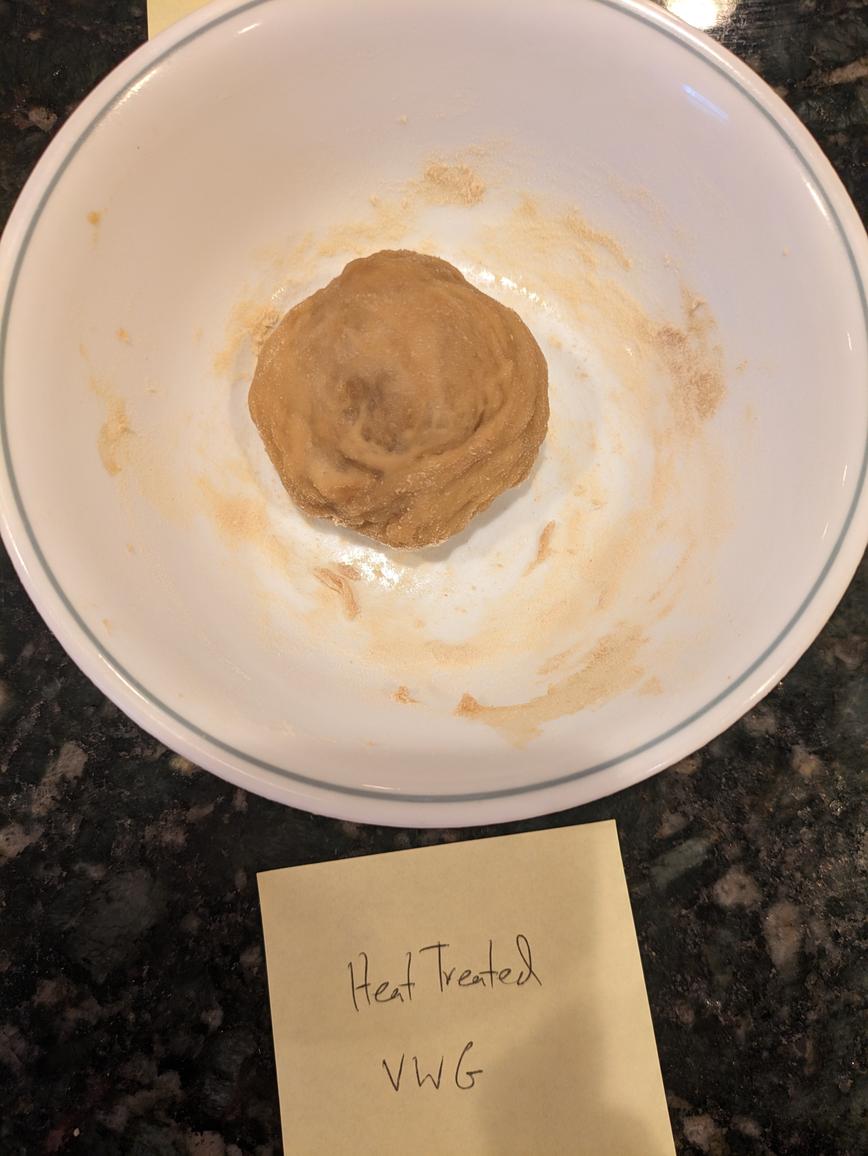

3b. Vital Wheat Gluten (Heat Treated)

This is the final flour that cannot be consumed raw. Heat treating can also be done by microwaving in 30 second intervals.

Interestingly, I noticed that vital wheat gluten seemed to brown quite a bit more in the oven as compared to the white flour or whole wheat. It also took more water than the original VWG as expected - about 31 g for 30 g flour. This was the first one to have more water than flour now.

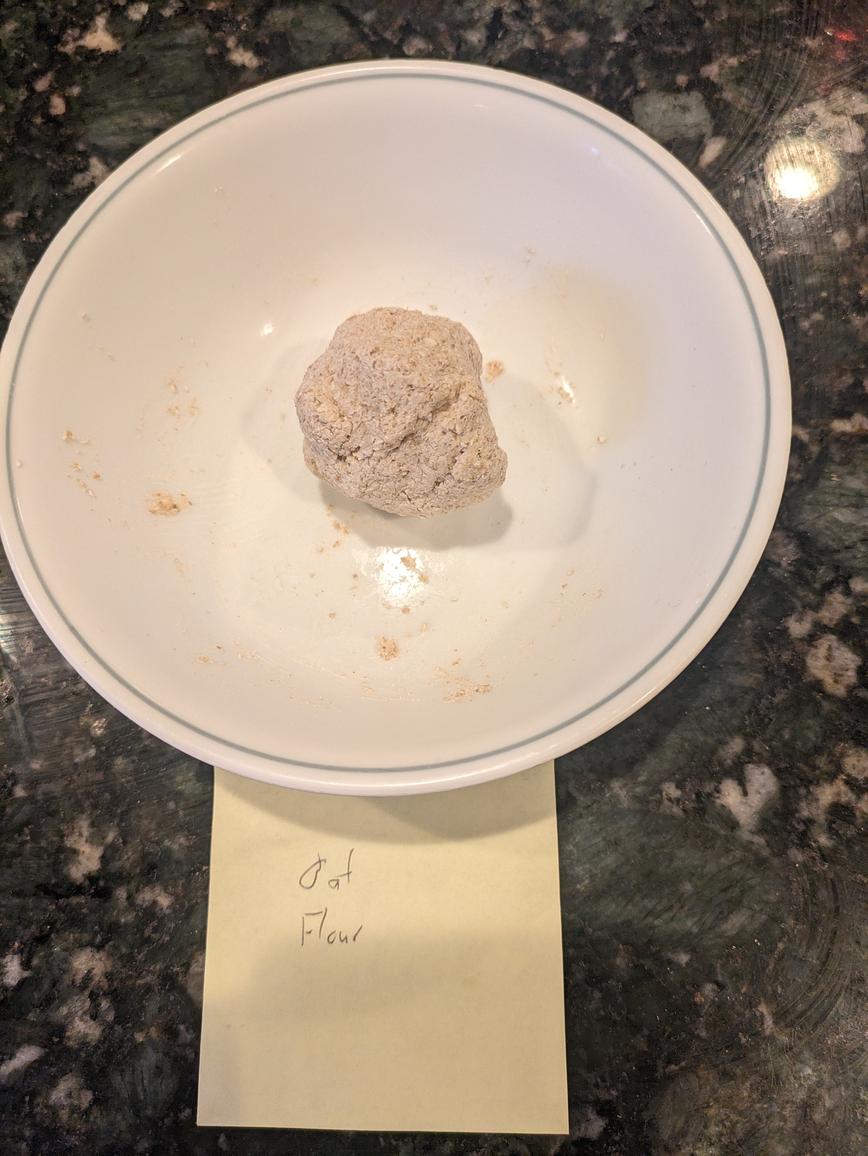

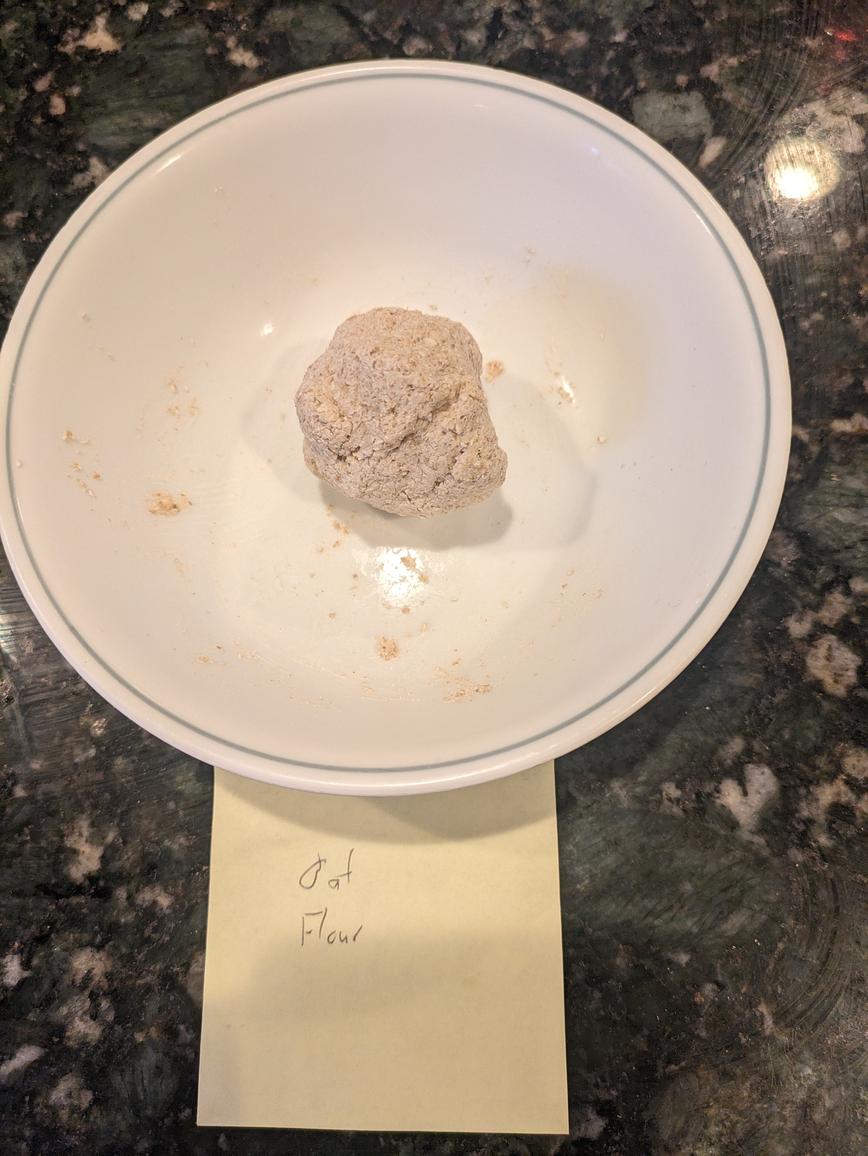

4a. Oat Flour

Oat flour is a very common healthy flour substitute that myself and others tend to use. It's cheap (if you make it yourself by grinding up quick or rolled oats), high in fiber, can be eaten raw, and gluten free. My oat flour here is just store brand quick oats that I blended myself in my food processor, which may be not as fine as storebought oat flour.

Oats also tend to soak up a lot of moisture, especially if you let the dough chill in the fridge for a little bit after mixing it. Meaning, you may want to keep the dough slightly sticky, as it'll absorb more water while it chills. My assumption here is that it will need a bit more water than the whole wheat flour though.

Turns out, 30 g of oat flour needed exactly as much water as whole wheat flour, 22 g. I left the dough slightly sticky though, as more water will be absorbed by the oats while it chills. The flour mixed well with the water to form the dough, and it instantly smelled like bland oats as soon as you started adding the water.

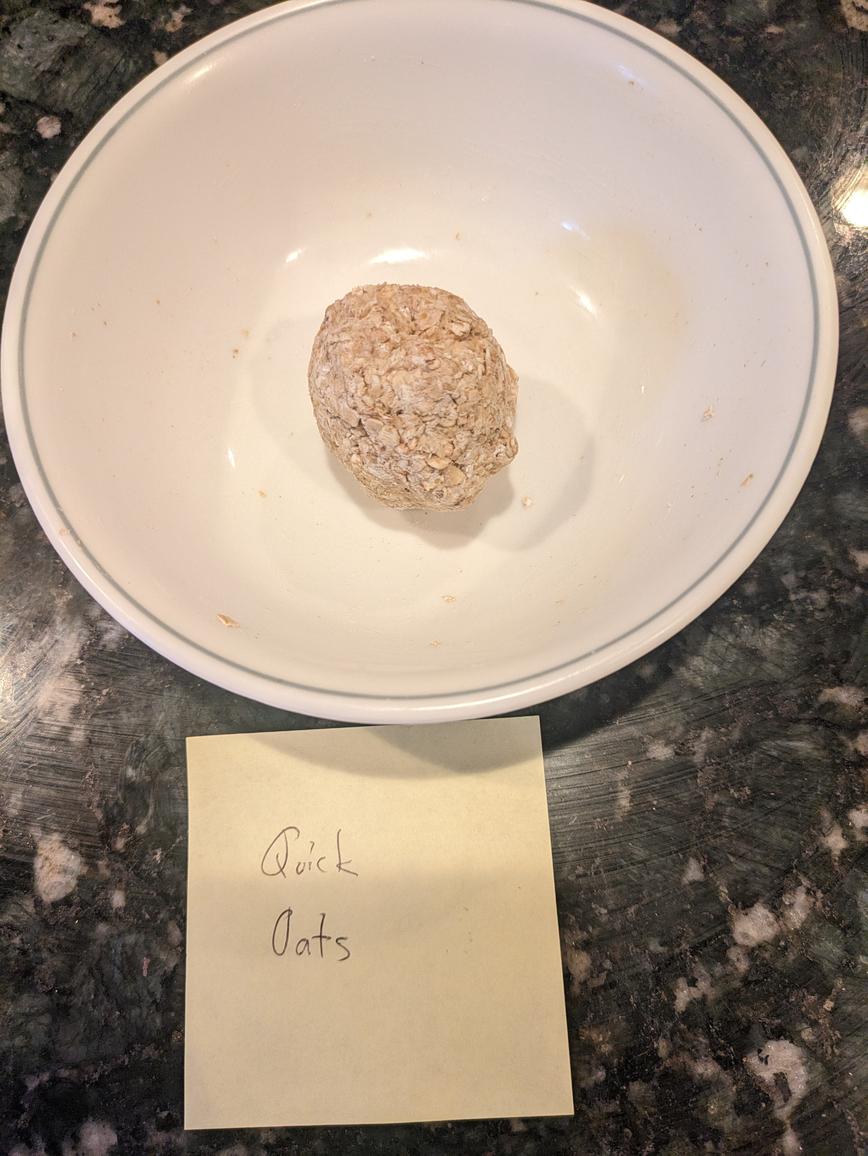

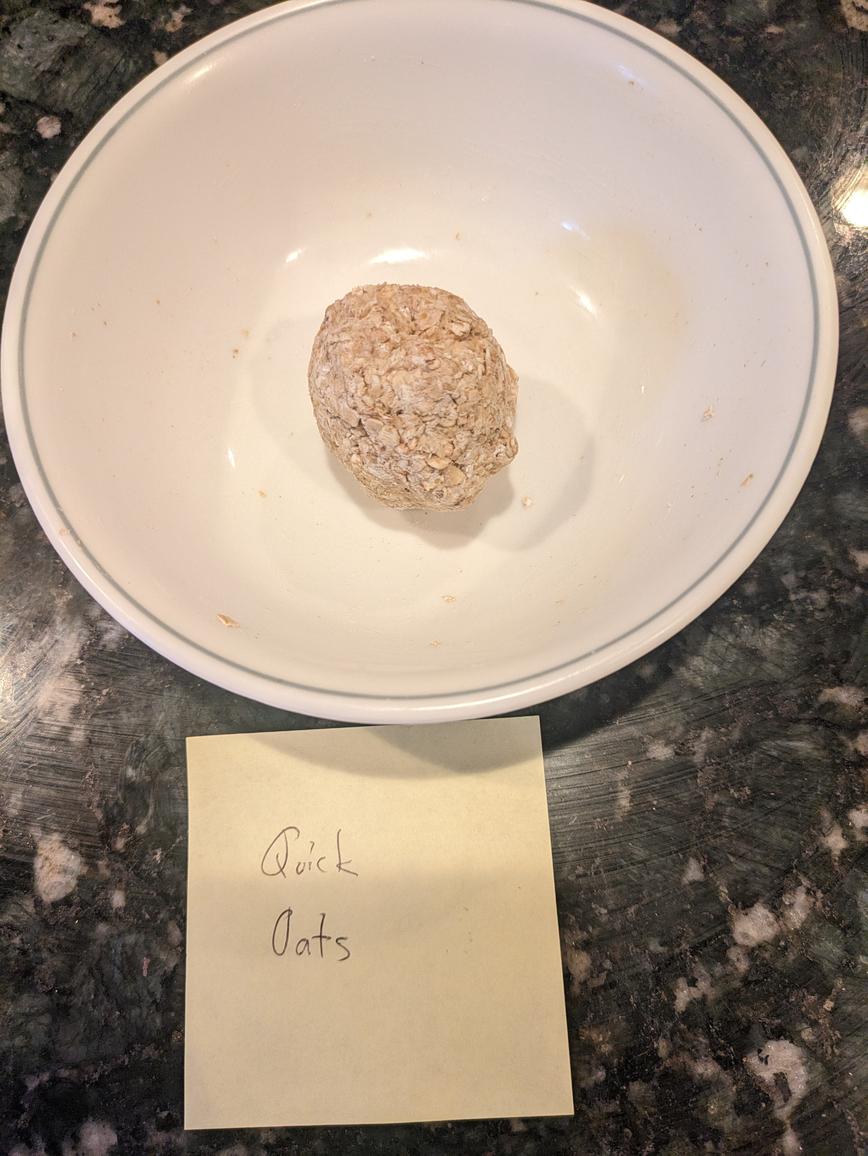

4b. Quick Oats

Since oat flour is just ground up oats, I wanted to see if using whole quick oats would yield different results. I don't have any rolled oats on hand, but I would assume that these would yield similar results.

The whole quick oats ended up taking in less water than the oat flour, only 20 g for the 30 g of quick oats. My guess here is that with less surface area, since the oats are not ground up, the oatmeal wasn't able to bind to as much water. Like with the oat flour above, it was left slightly sticky to give room for delayed water absorption.

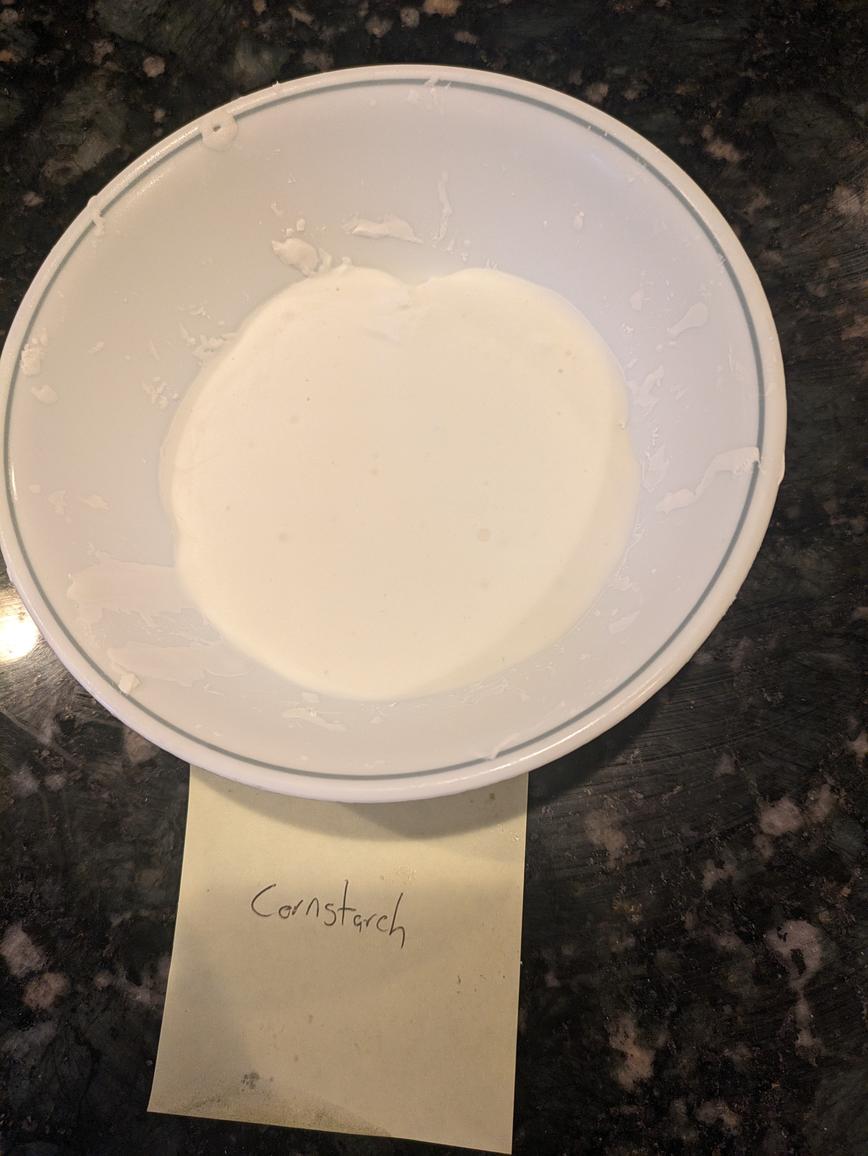

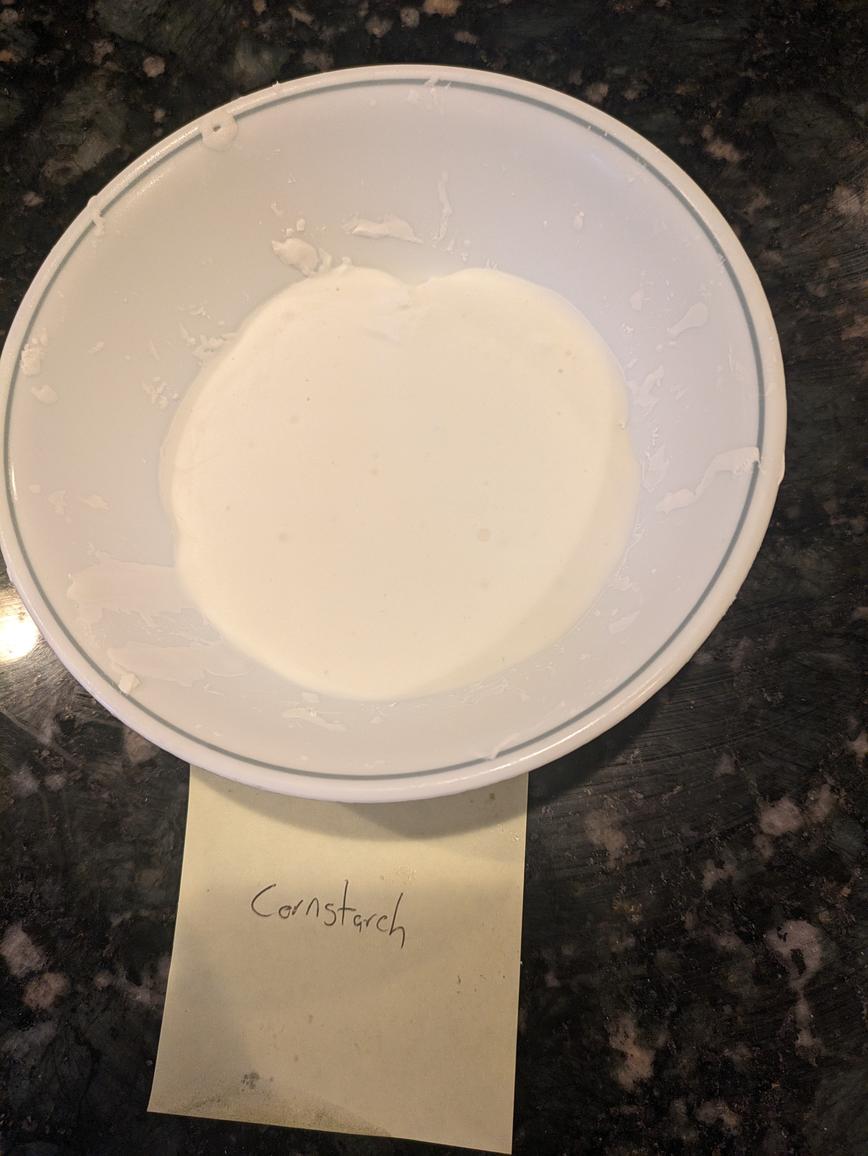

5. Cornstarch

Cornstarch is almost never used as the sole flour in a recipe (except in sequilhos). Rather, I typically see a little bit used when oat flour is the main flour in a recipe, in order to help with the texture and replicate the feeling of a flour with gluten, while still being gluten free.

Typically, cornstarch is used more in cooking than baking. It, along with flour, are typically used to thicken a sauce in a dish. A common conversion is 1 tbsp cornstarch for every 2 tbsp all purpose flour, so it would be interesting to see if that holds up here.

This was a super weird one to make. I don't think I've ever see anything be so dry and so wet at the same time; I didn't think that was possible. I ended up with about 26 g of water for 30 g of cornstarch, but I originally overshot the water, and had to double everything to compensate.

As soon as you start mixing in water, it gets super clumpy and hard to mix; you need to use your hand. But then almost instantly, you end up with a putty or glue. This felt like an elementary school science experiment. I was able to clump everything together in my hand to form a reasonable dough ball, but as soon as I put in back in the bowl it turned to a pastey liquid.

Turns out that I accidentally created Oobleck lmao. This was fun to play with, but not to eat. Into the garbage it went.

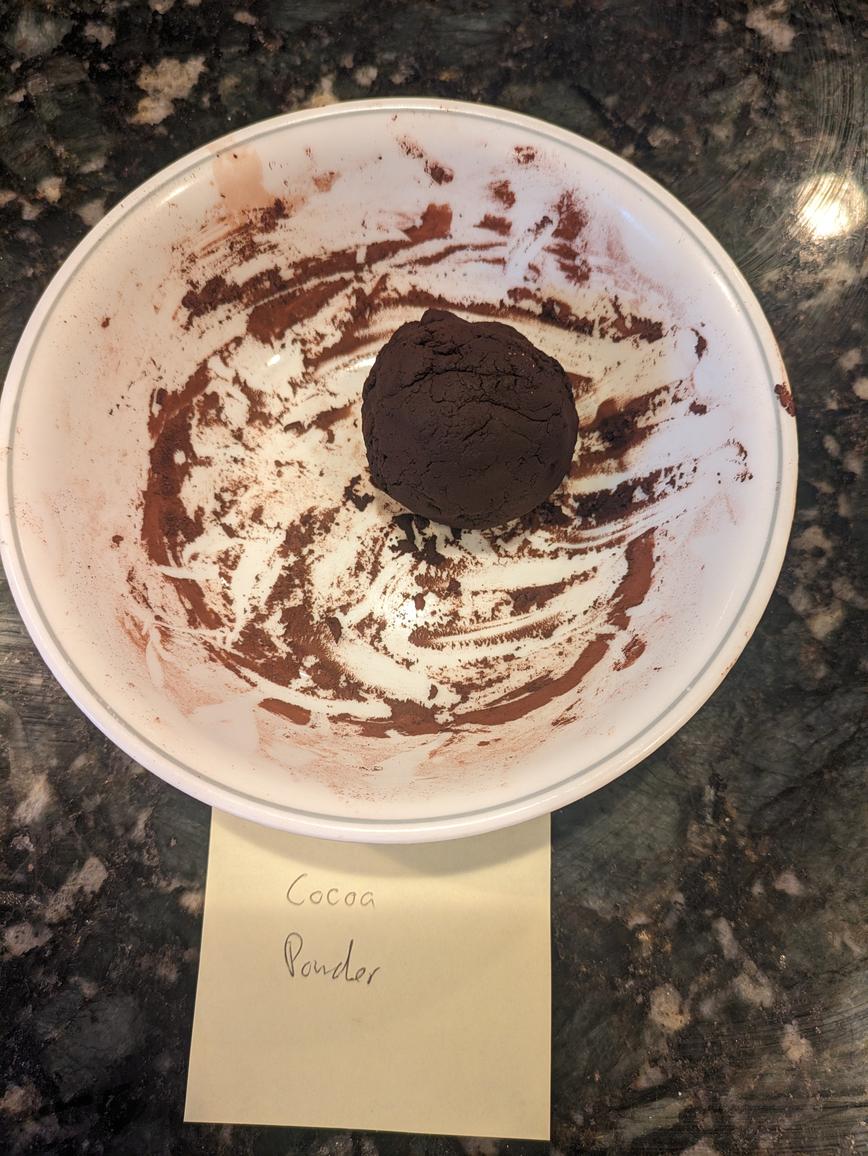

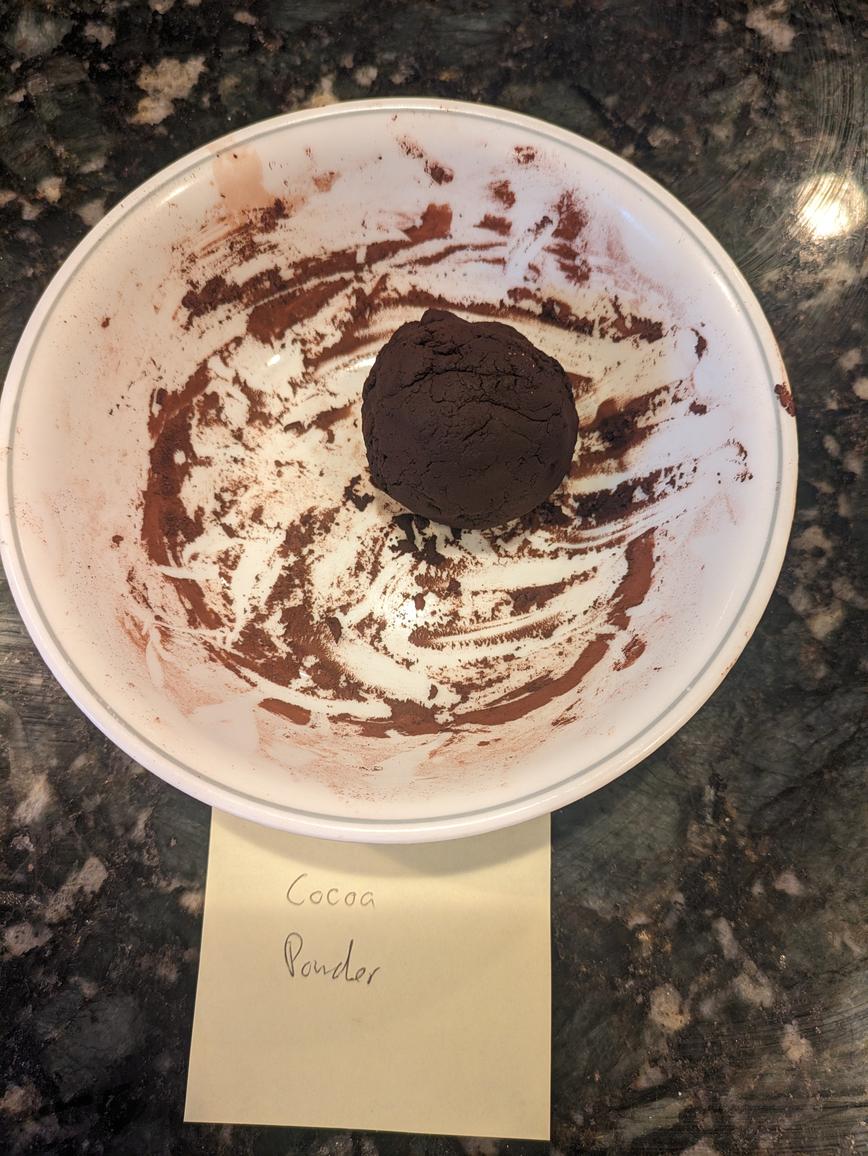

6. Cocoa Powder

While not a flour, cocoa powder is a powdered solid ingredient that can certainly act as a flour in small amounts. Look at brownies; about the same weight of flour and cocoa powder can be used in a recipe. Knowing the conversion ratio here should be helpful in swapping out all purpose or oat flour in place of cocoa powder for a chocolate flavor.

I won't be testing cacao or carob powders here, but I would assume that these would yield similar results. Also, I only have Dutch process cocoa on hand, but I would assume that natural cocoa would also be similar.

I knew that cocoa needed a bit of water and stirring to get it fully hydrated, but I didn't expect it to be this much. 40 g of water for 30 g of cocoa powder is the highest amount of water so far. At first, the water doesn't look like it's doing too much other than making the color a little brighter. But as you add more water and stir, you all of a sudden get a dark brownie colored ball with an intense chocolate smell.

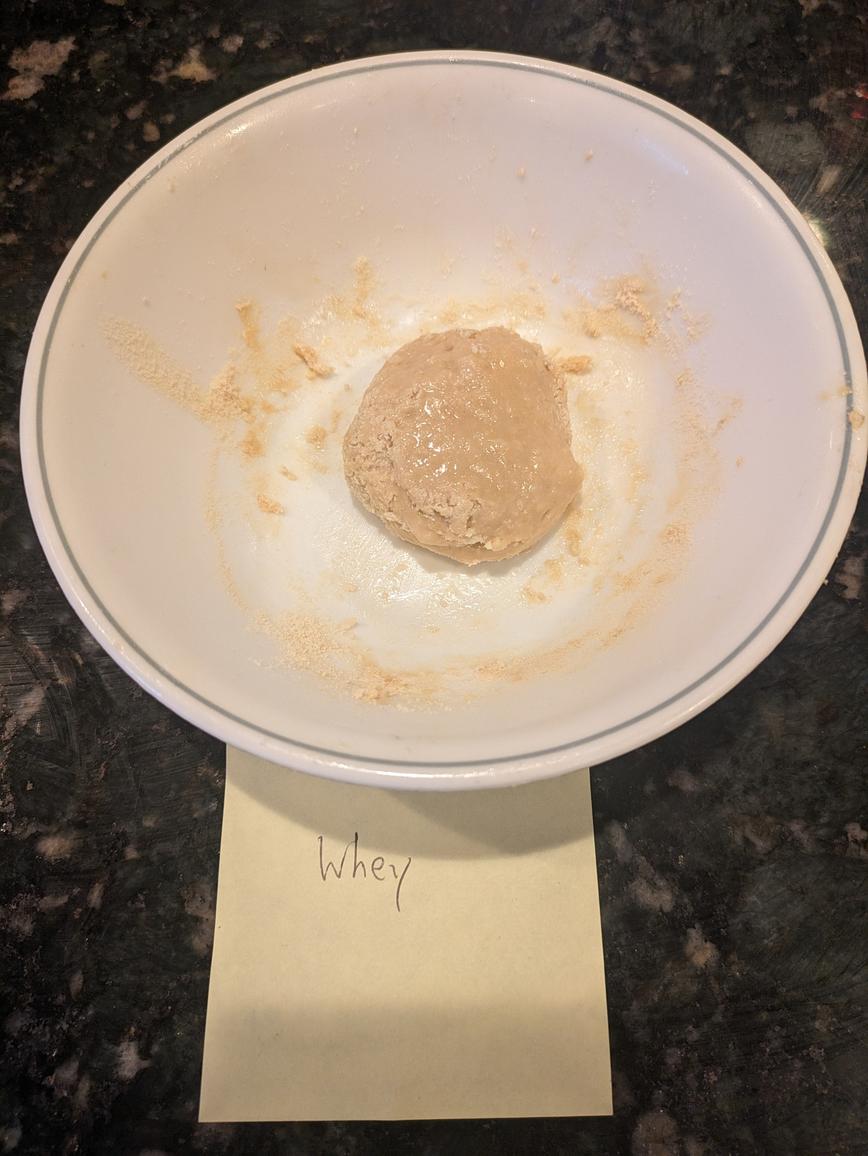

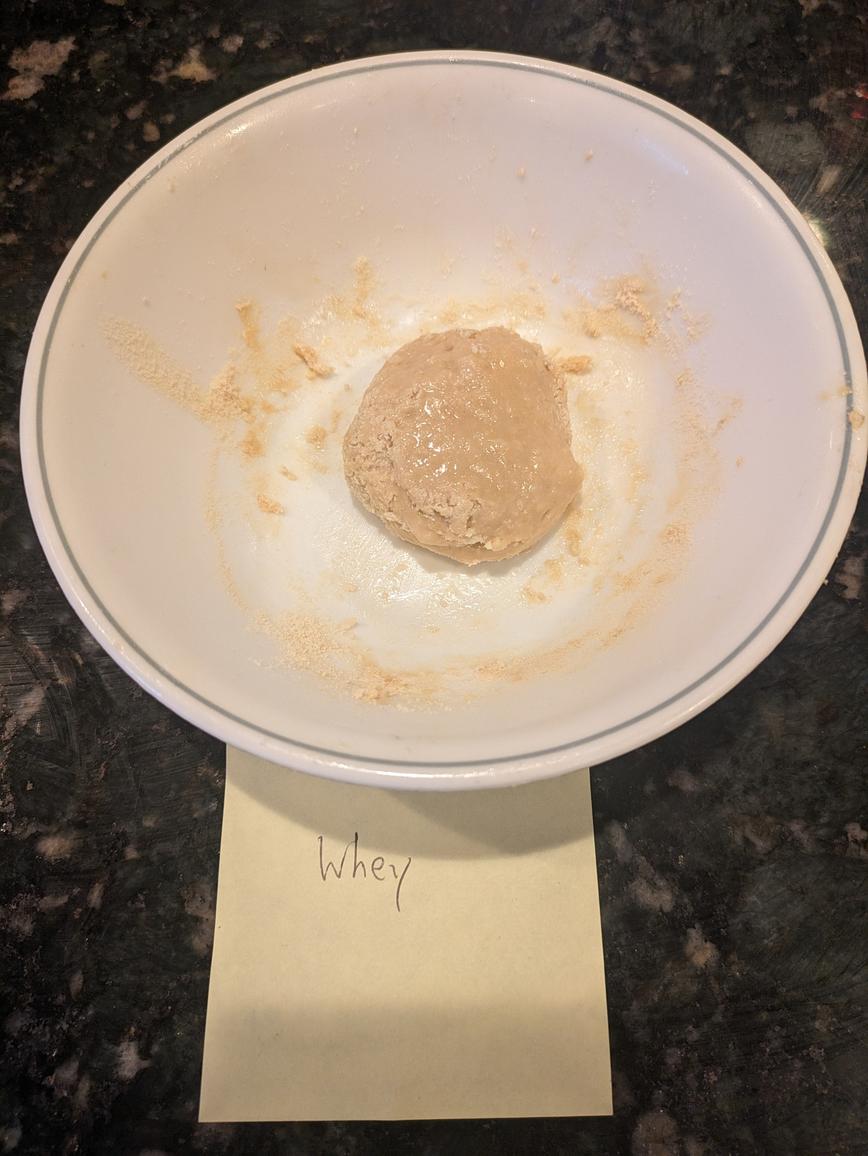

7a. Whey Protein Powder

Whey protein is the more common type of protein powder as compared to casein. It's known for not binding to water very well, which is why it works so well in a protein shake. It's basically the opposite as casein in terms of using as a flour. A common question in many protein powder recipes is if you can substitute casein for whey, and the answer is almost always a no, which I hope to show below.

The 30 g of whey protein only needed 14 g of water, and even then it was still a bit sticky. This is by far the lowest on the list so far, and I'm predicting that it will stay that way. Add too much water and whey can easily mix in cohesively to the liquid, making very poor as a solid flour replacement, but great for dissolving into something.

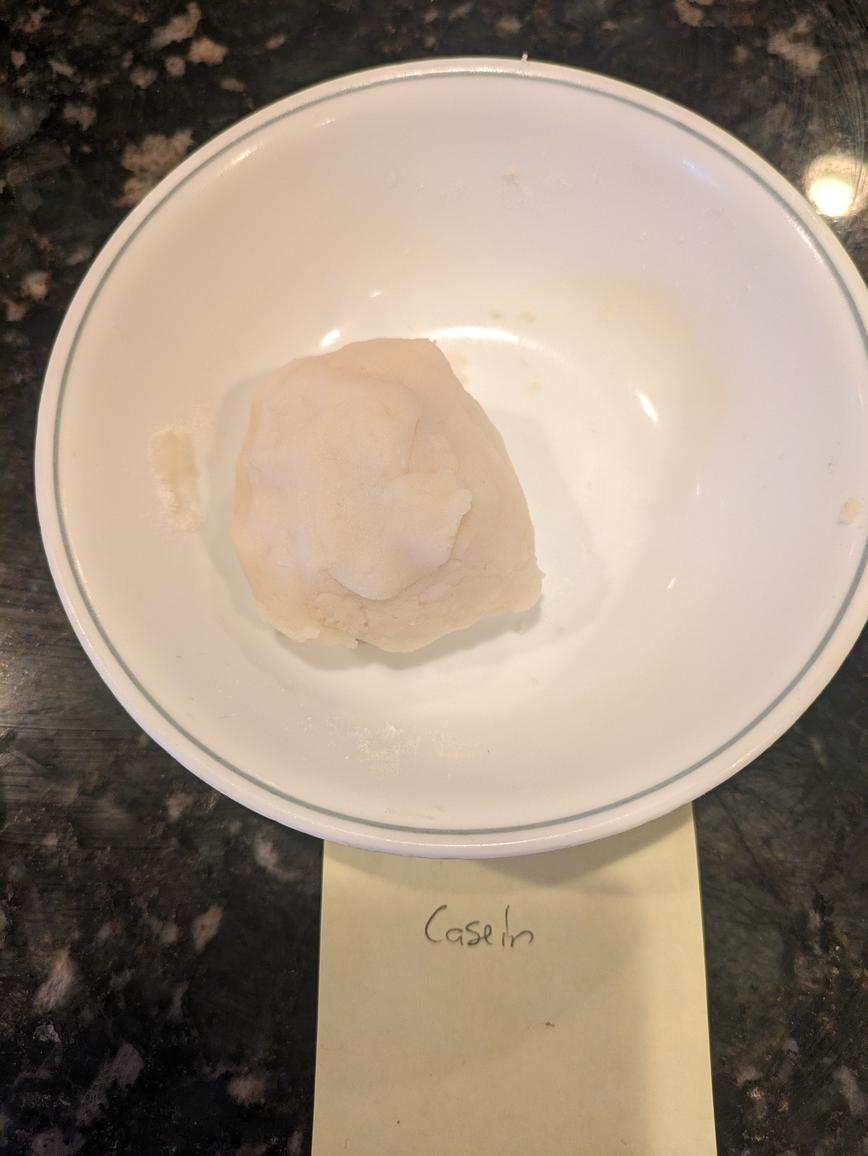

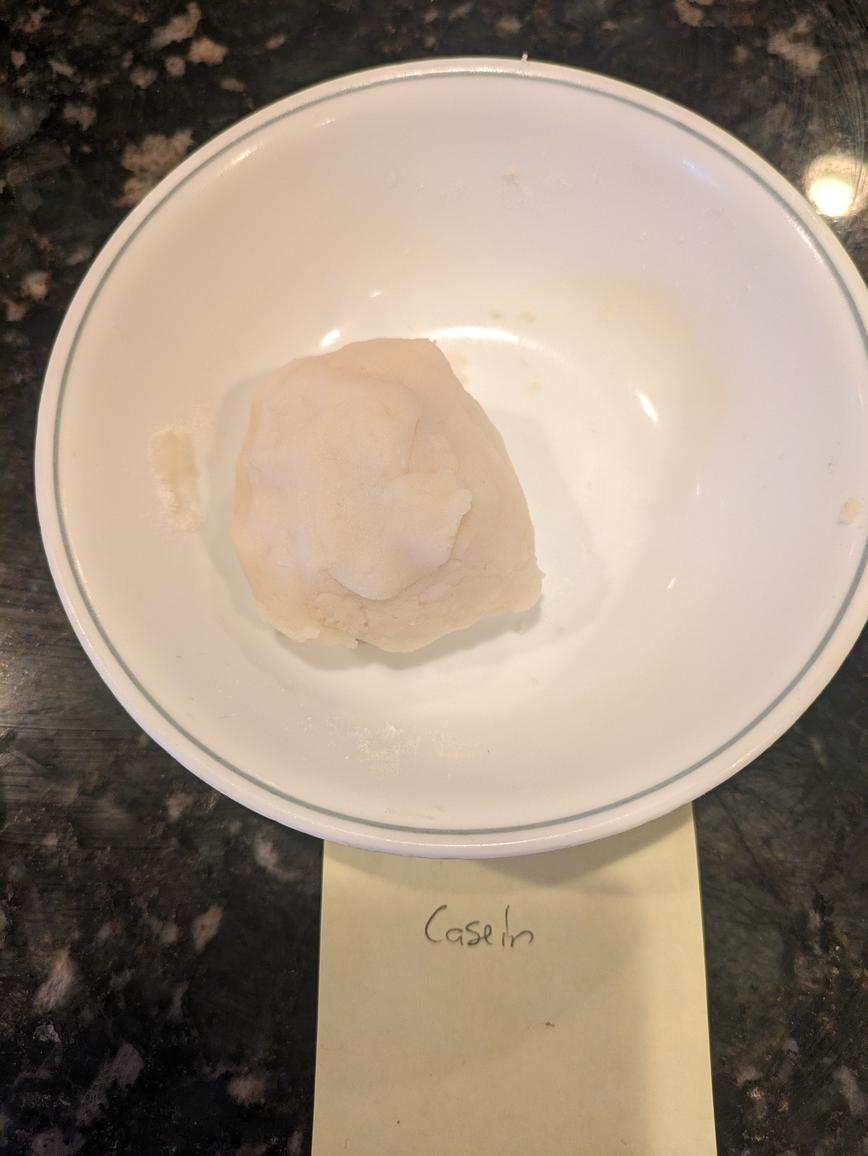

7b. Casein Protein Powder

Casein protein is the lesser known milk protein, with the other being whey. It acts more like a flour, holding on to water very well, which is why it would be a good ingredient in a cookie dough, and a bad ingredient in a protein shake (it would clump up). Casein absorbs a lot of liquid; my estimate is that it will fall somewhere between oat flour and coconut flour.

As I predicted, casein and whey are basically opposites. For 30 g of casein protein, 70 g of water was needed. That's 5 times the amount of water as the whey, with the 2 protein powders currently being the most and least absorbent tested so far.

The next time you try to replace casein with whey (or vice versa), keep this in mind. Use casein to thicken and make something more solid, and use whey to add more protein without changing the consistency too much.

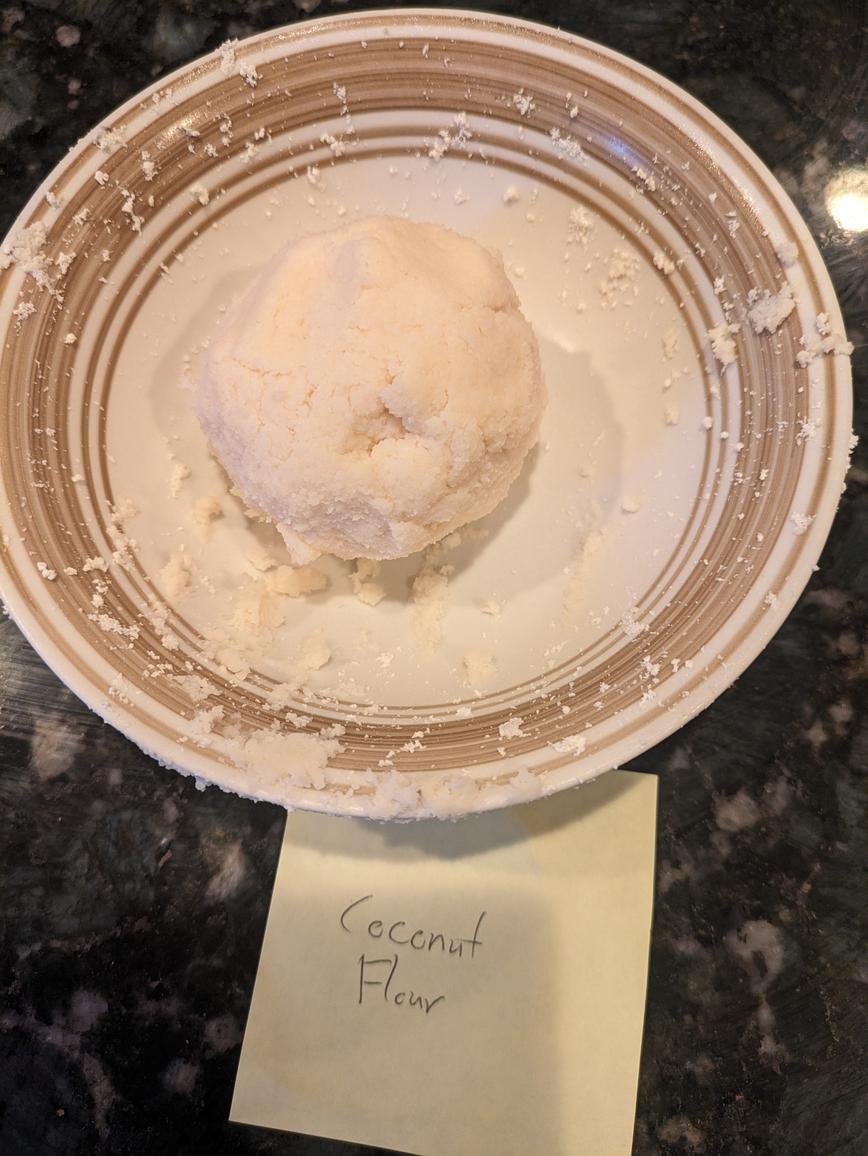

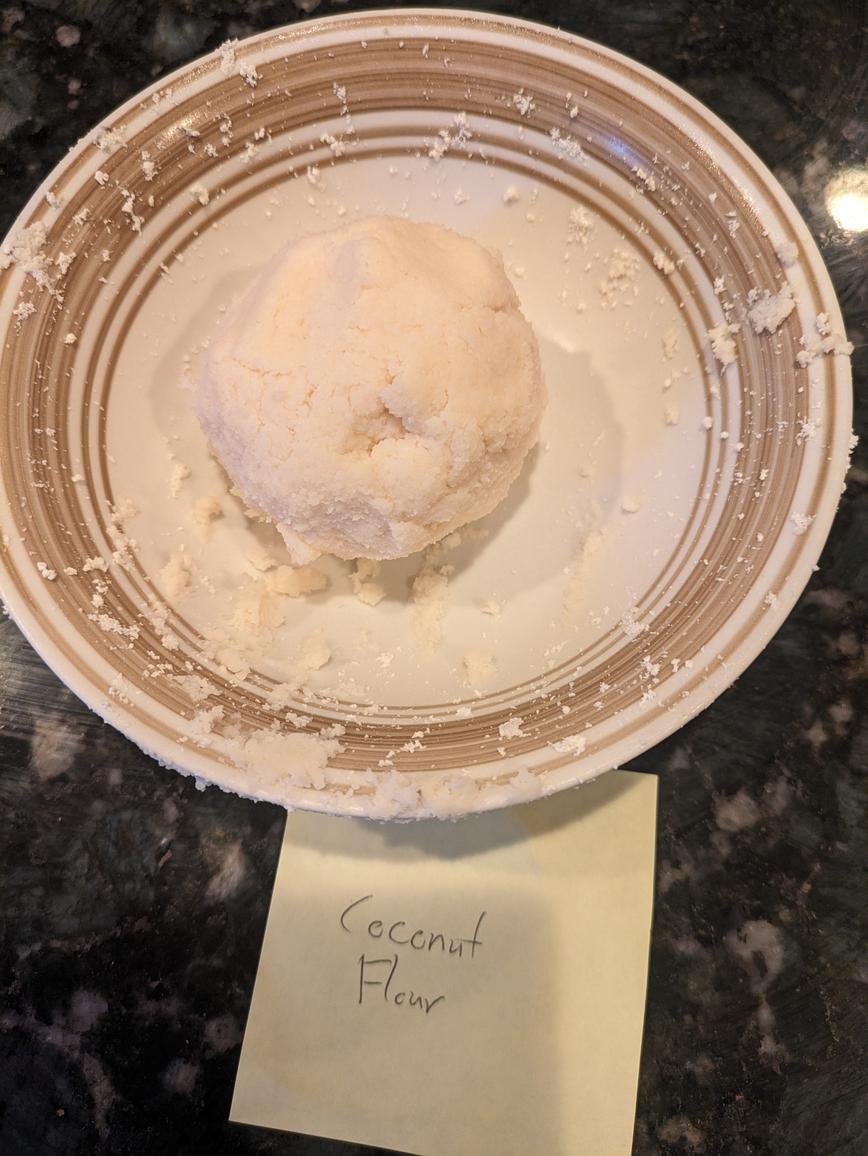

8. Coconut Flour

Coconut flour is another gluten free flour alternative. It's made from dried and defatted coconuts, similar to how peanut flour (PB2 or PBFit) is made. It's low in fat and carbs and high in fiber, as well as having a slightly sweet taste.

Coconut flour is also widely known for absorbing a ton of liquid. I've heard estimates that replacing that using 1/4 cup of coconut flour is equivalent to 1 cup of all purpose flour, meaning it would absorb 4 times as much liquid.

Coconut flour is insane; I don't know how it could hold on to water so well. It took 120 g. of water for just 30 g of coconut flour. That's 4 times the amount of water by weight than coconut flour. As such, the dough ball was easily the biggest that was tested. Recall that the AP flour needed only 17 g of water, which is 7 times less than the coconut flour. I suppose that using 1/4 of coconut flour for every cup of standard flour isn't as ridiculous as it sounds.

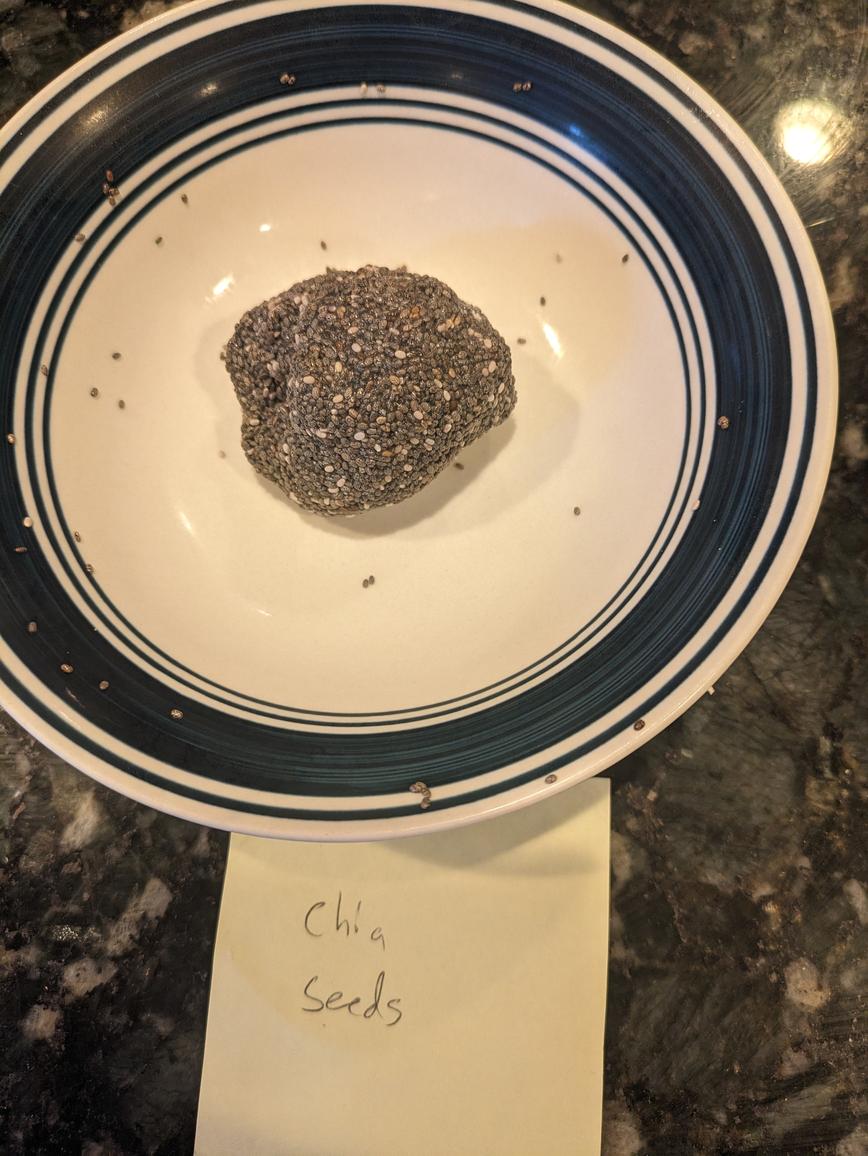

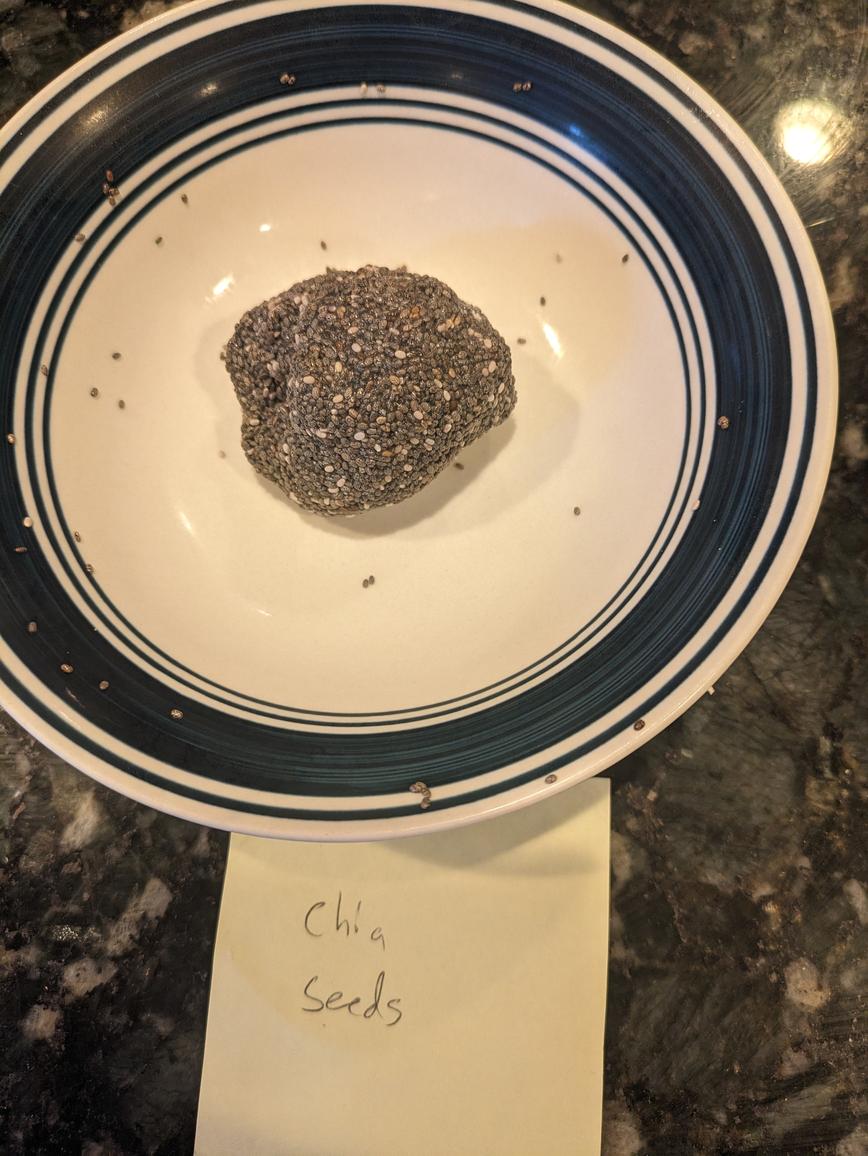

9. Chia Seeds

Similar to flax seeds, chia seeds are also very high in Omega-3s and fiber. There is a strong difference in texture though; chia seeds are normally consumed whole, whereas flax seeds tend to be ground into a flour. You could blend the chia seeds, but here I'll be using whole chia seeds.

It should be noted that chia seeds swell up with water, which is what thickens overnight oats. This can take a little bit though, so while the dough will at first look too wet, you'll need to undershoot the water a bit to end up at the consistency you desire. Oat flour is similar in this regard, but chia seeds are a much more extreme version of the same concept.

Whole chia seeds was admittedly a weird test; moreso to see just how chia seeds absorb water. I added 30 g of water to 30 g of chia seeds in a bowl and stirred. It looked way too liquidy at first; but after 5 minutes, I had a solid ball of dough that I could handle and roll.

A typical chia egg is a 3:1 water to chia seed ratio by weight, whereas this was a 1:1 ratio. I basically made a dry chia egg, and showed why you need to let it sit for a few minutes (for the chia seeds to gel) before adding to a recipe as an egg substitute.

This little ball also has 10 g of fiber. The majority of American's aren't consuming enough fiber; the RDA for men and women respectively are 38 g and 25 g, but the average American adult only consumes 10-15 g of fiber daily. I'm not saying eat chia dough balls, but maybe try adding chia seeds into your diet.

10. Peanut Flour

Peanut flour, similar to coconut flour, is made by defatting and drying peanuts, and grinding them into a flour, leading to a product that's fairly low in carbs and fat, but high in protein (basically a vegan protein powder).

It's typically known by the brand names PB2 or PBFit, which are versions of peanut flour with a little bit of salt and sugar added to it. The brand I'm testing today is the Walmart GV Powdered Peanut Butter. My assumption is that it will absorb quite a bit of water, but not nearly as much as the coconut flour.

This one surprised me a bit. For some reason, I expected peanut flour to be able to hold on to a lot of water, similar to the cocoa powder, but it was a bit less. The 30 g of peanut flour only needed about 29 g of water to make it into a dough

11. Flaxmeal

Flaxmeal, also known as ground flaxseed or flaxseed meal, is made by grinding together whole flaxseeds until a flour is formed. It's high very high in Omega-3 fatty acids as well as fiber, while being low in carbs and gluten free.

Typically not used on its own, flax is usually added as an additional flour in small amounts in keto or GF recipes; however, I wanted to isolate it here and test how it would be as the sole flour.

For some reason, I expected ground flax to have results closer to chia seeds. But it definitely took in less water; only about 21 g of water for 30 g ground flaxseed. It had a cookie dough like texture, but certainly hardened in the fridge. It turned into something you could crumble (which I did over a bowl of yogurt lol)

12a. Almond Flour

Almond flour is one of the most common grain free keto flours I see used in recipes. It's highly nutritious, but I tend not to use it as it's faily expensive. Almond flour is made by blending blanched almonds (almonds with the skin removed) in a food processor until very fine. I'm assuming that almond flour won't be able to absorb quite as much as peanut flour, but about as much as the oats.

This one surprised me. For some reason, I expected almond to take in more water than the wheat-based flours. In fact, it was nearly the same. The 30 g serving of almond flour needed about 17 g of water to come to a similar consistency as all the rest.

12b. Almond Meal

The only difference between almond meal and almond flour is that almond meal includes the almond skins; it doesn't use blanched almonds. Almond meal can be purchased in a bag, but it is very easy and often cheaper to make your own almond meal by just blending whole almonds.

Almond meal is coarser due to the skins, and is more like finely chopped nuts than a flour. I'm thinking this test should yield similar results to oat flour vs quick oats; comparing a more finely ground flour to a coarser solid.

Almond meal was a weird one. To 30 g of almond meal I added 20 g of water and mixed. It was simultaneously too dry to come together and too wet where water was seeping out of it. I did grind up my own almond meal, so maybe the issue was that it wasn't fine enough? Either way, almond meal cannot be a flour substitute like almond flour can.

13. Millet Flour

Millet is a type of grain that is gluten free, making it a great GF flour alternative to those with celiac disease. Millet can also be eaten raw, making it great for no bake recipes as well. It looks, smells, and feels similar to all-purpose flour, but with a slight yellow-ish hue. I expect it to have an absorption of about the same as white or whole wheat flour.

This aligned with my expections; 20 g of water was added to the 30 g of millet flour in order to become a workable dough. Being a gluten free grain, I would assume this means that you can probably replace all purpose flour for millet flour in a 1:1 ratio in any baked goods and likely be okay.

14. Hemp Seeds

Hemp seeds are a kind of coarse seed that is not ground, similar to chia seeds or whole flax seeds. It has a similar texture to almond meal, if not even more coarse. While chia and flax seeds are known for absorbing a lot of water (think a chia egg or flax egg), I've never heard of a hemp egg. I'm assuming this won't go well.

As predicted, yeah that didn't work; 15 g of water was added to the 30 g of hemp seeds to attemp to make a dough. Just like with almond meal, this didn't come together at all; the "flour" was too course to bind to the water, and instead became a wet sticky mess, no matter how little or much water I added.

15. Psyllium Husks

I'm very interested to see what happens here with the psyllium husks. Psyllium husk is a type of soluble fiber that's used a lot in gluten free bread making to mimic the feel of gluten. Typically, it will be mixed with water and left to rest for a few minutes to gel before adding into the dough, like in my Gluten Free Millet Bread. Since it's known for hydrating and gelling up, I'm predicting this will take a lot of water.

As assumed, the psyllium husk was able to absorb a lot of water; 2.5x its weight. For 30 g of psyllium husk, I was able to mix in 75 g of water in order to become a workable dough. Not quite as much as coconut flour, but it edges out casein protein powder for the silver medal. Not that I'd ever use psyllium husk as a flour; you'd probably be making a beeline to the bathroom if you did.

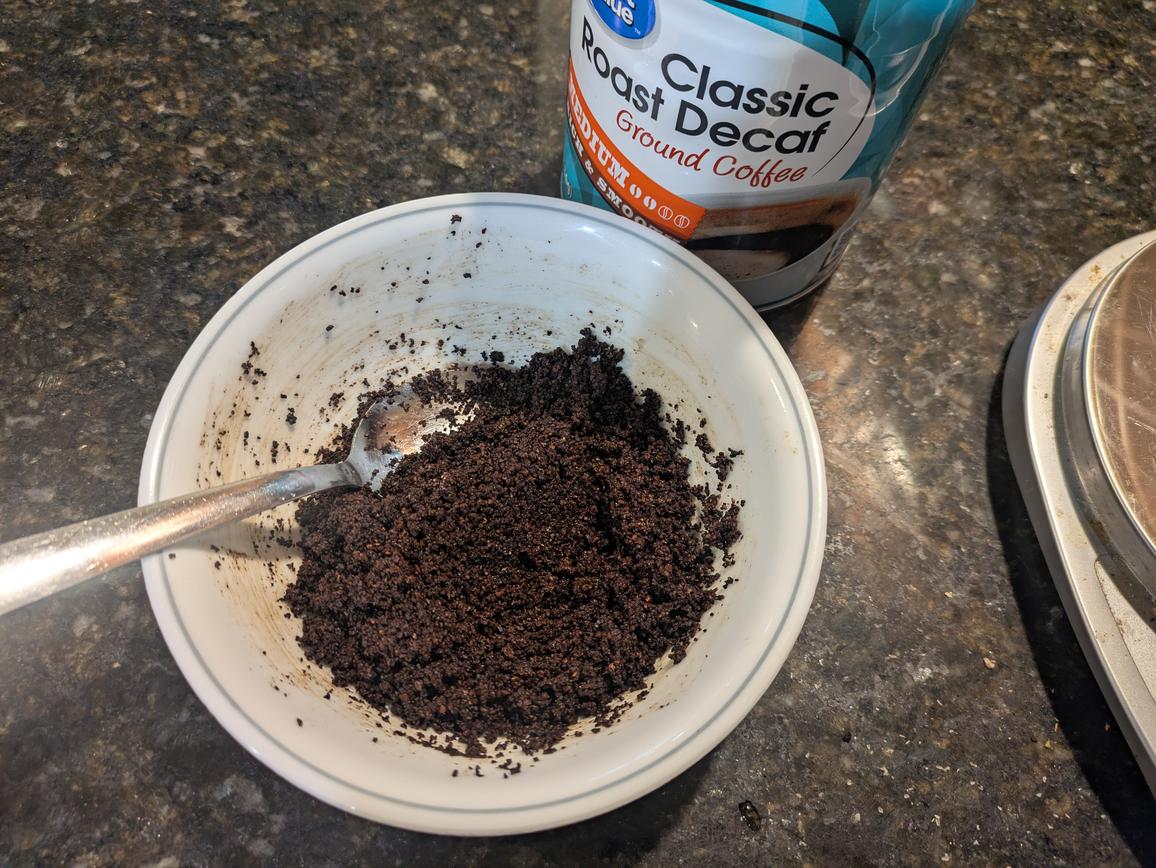

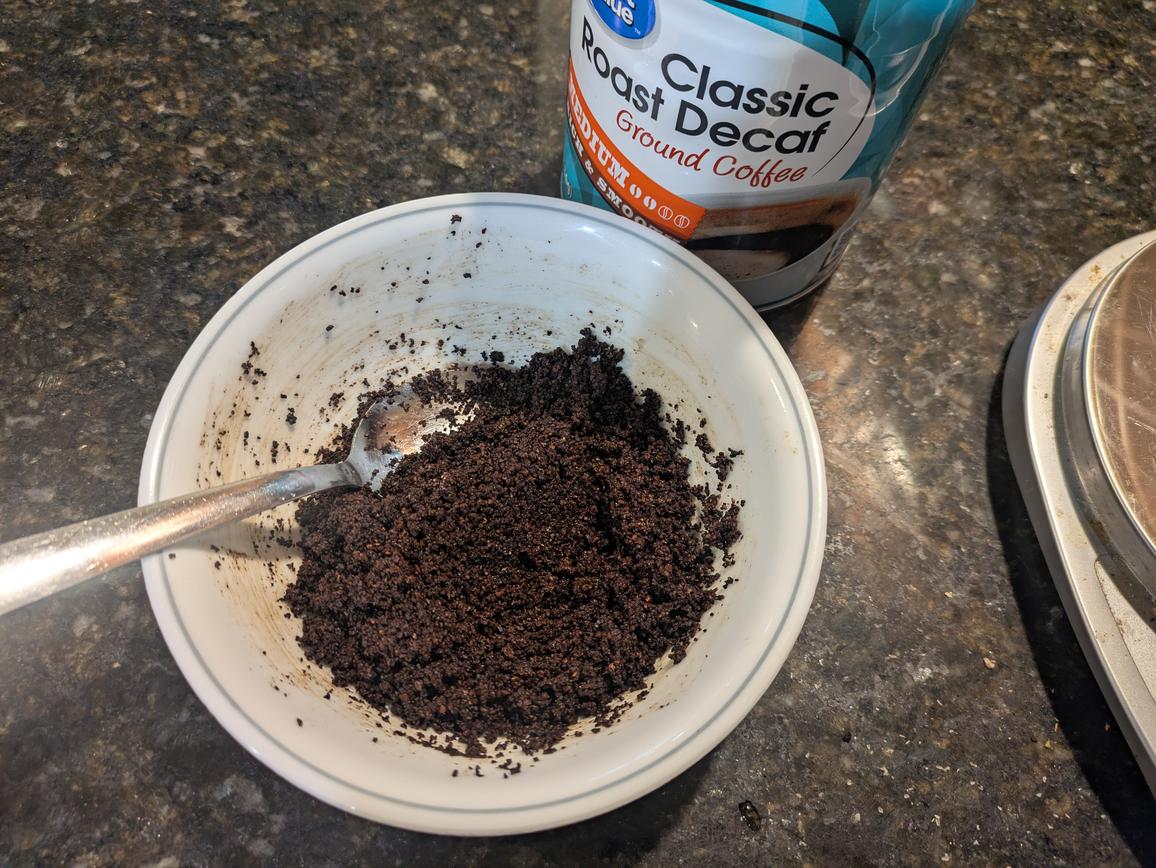

16. Ground Coffee

Using (decaf) ground coffee, I'm going to attemp a coffee ball. I'm guessing this will fail, as I've seen leftover wet coffee grinds in the garbage can before, and would assume that this would not be able to bind together like the others on this list.

For 30 g of ground coffee, I added 15 g of water and stirred. This felt like holding wet pebbles. There's no way to get this to come together as a cookie dough texture. The texture is very coarse, and the mix feels too dry to stick, but too wet where it's sticky, somehow. Weird.

17. Granulated Sugar

Finally, sugar. This is a stupid one, I know. Sugar is known for dissolving in water, not binding to water like flour does. But I was curious and figured what the heck.

I only added 5 g of water to 30 g of sugar to end up with this wet mess. I basically started to make sugar syrup in a bowl without heating it up. Which I attempted to do; turns out you can caramelize this small amount of sugar just by microwaving for about 45 seconds. Imagine the lazy creme brulee you can make knowing this.

Results

Below is a table of the results, with the grams of water needed to form a dough ball for 30 g of each of the flours tested above.

I've decided to normalize it now for water instead of flour. The below table is based on 30 g of water, and how much flour it would take to make it a dough ball. That way, you can more easily see how you would need to adjust your recipe accordingly.

Conclusion

From the tables above, you can get an an estimate of how to replace one type of flour with another in a recipe. I was most interested in the coconut flour, which is able to absorp so much water. I can get a bag for only $4 a pound, and since you need so little, I've found that coconut flour is actually a great cheap GF flour replacement. Typically I see almond flour being used, but coconut is just so much cheaper.

Another great cheap alternative is oat flour, which is probably cheaper than coconut, and also much more versatile. I use either oat flour or quick oats all the time; that's only about $4 for a 42oz canister of oats. Oats are rich in fiber, provide a great nutty taste, and can hold onto a bit of moisture.

Finally, I hope I've demonstrated the difference between whey and casein protein powders, and why you simply can't just sub one for another in a recipe. If you are looking to add protein to something, start with a 50/50 blend of whey/casein, and go from there. Whey can help a cake rise, but it will dry it out. Casein, on the other hand, will keep it moist, but might make it dense. This is why a blend is normally a safe bet.

I've a Python script where you can enter the flours you are converting from and to, along with the amount of the original, in order to find an approximate amount to use. Click here to download the file to run it yourself.

Now if you'll excuse me, I'm about to blend all these dough balls together to create some weird Frankenstein cookie dough.

Ingredients

Epilogue

So cookie dough didn't end up happening...it was too liquidy. So instead, I made it into a chocolate spread. It's surprisingly delicious and high in protein, like a high protein and low sugar/fat nutella.

I just blended together all the dough balls with some sugar free syrup, a pinch of salt, cinnamon, almond extract, nut butter, and greek yogurt

It's a really good spread on toast or in oats that I'd honestly consider making again lol. Each serving is about 2 tbsp or 32 g.

Nutrition Facts

------------------------------------------

Sources

1. How to substitute whole wheat for white flour in baking

2. Vital Wheat Gluten

3. Quaker Oat Flour 101

4. What's the maximum amount of water that oats can absorb?

5. How to Use Flour or Cornstarch to Thicken Sauce, Gravy, and Soup

6. Effect of whey and casein protein hydrolysates on rheological, textural and sensory properties of cookies

7. Everything You Need To Know About Baking With Coconut Flour

8. How to Use Almond Flour As a Replacement

9. Almond Meal vs. Almond Flour. What's the Difference?

10. How To Use Protein Powder CORRECTLY (Whey vs. Casein)

11. How To Make Oobleck

In making recipes, it's helpful to know when you can substitute one kind of flour for another, and what effects it will have on your finished good. Here, I'll be taking 30 g, or about 1/4 cup (volume may vary) of each flour, and mixing it with a variable amount of water until I have a cookie dough like consistency, and letting it chill in the fridge for an hour. I want something that is not too dry and not too sticky, and that holds its shape and can be formed. Each of the flours will absorb water differently, so if you are swapping one for another in a no bake recipe, this will be a helpful page for you.

List of Flours Tested

1. White Flour

a. Not Heat Treated

b. Heat Treated

2. Whole Wheat Flour

a. Not Heat Treated

b. Heat Treated

3. Vital Wheat Gluten

a. Not Heat Treated

b. Heat Treated

4. Oatmeal

a. Oat Flour

b. Quick Oats

5. Cornstarch

6. Cocoa Powder

7. Protein Powder

a. Whey Protein Powder

b. Casein Protein Powder

8. Coconut Flour

9. Chia Seeds

10. Peanut Flour

11. Flaxmeal

12. Almonds

a. Almond Flour

b. Almond Meal

13. Millet Flour

14. Hemp Seeds

15. Psyllium Husks

16. Ground Coffee

17. Granulated Sugar

Note About Heat Treating

As you may or may not know, wheat based flours cannot be consumed raw due to the risk of E. Coli. Heat treating the flour typically involves cooking it in the oven, microwave, or on the stove until it reaches a temperature of 160F, where all the bacteria would be killed off. The flour then can be enjoyed in a raw dessert, such as edible cookie dough.

As for the testing, I'll be baking a tray of the flour at 300F for about 10 minutes, or until lightly browned and an instant thermometer reads 160F. Note that I'll be using weighing out 30 g each of the heat treated flours post heat treatment, not before.

Testing

1a. White Flour (Not Heat Treated)

White flour, or all purpose flour, is the original flour. It's probably the one you're most likely to have in your kitchen. I avoid using it in recipes, as its highly processed, bleached, and low in nutrients.

It serves as a good basis though if you'd like to swap white flour for a more nutritious option. Here, I'm using a general store brand bag of white flour.

Right away, I've realized that the wheat based flours will be the most difficult and least accurate. They stick more, and their doughs will more closely represent bread dough than cookie dough. For the standard white flour though, I found that 17 g was enough to bind 30 g all purpose flour.

1b. White Flour (Heat Treated)

I wanted to see if heat treating the flour would lead to any difference in the amount of water absorbed by the flour. As it's parially baked, some of the water would have cooked off, leaving a dryer flour able to absorb a little more water.

Turns out, 30 g of heat treated white flour was able to absorb about 20 g of water, which is a 16.2% increase. It's hard to tell if this is a significant difference, or just due to user error. Based on my hypothesis above though, it would seem that some of the water cooked out of the flour, allowing the heat treated version to take in more.

2a. Whole Wheat Flour (Not Heat Treated)

Whole wheat flour is a healthier option as compared to white flour. It is flour of the entire wheat kernel, leading to more protein, fiber, and micronutrients.

In making loaves of bread, I used to use about 320 g of water for 500 g all purpose flour. Now, when I make whole wheat bread, I use about 360 g of water for 500 g whole wheat flour. Therefore, I would assume that the whole wheat will take in more water. The brand of flour I'm using is King Arthur.

It took 22 g of water for 30 g of whole wheat flour, which is a 25.6% increase over the standard all purpose flour experiment. This would suggest that when substituting white for whole wheat flour, you should either use a little more liquid, or start with less flour and go based on the feel of the dough to see if you need to add more.

2b. Whole Wheat Flour (Heat Treated)

Again, just like with white flour, whole wheat flour cannot be consumed raw, due to risk of E. Coli. I wanted to again test if heat treating will make a difference from the trial above.

As expected, the heat treated whole wheat flour absorbed a little more liquid compared to the regular whole wheat flour - 23 g of water for the 30 g of flour, as compared to 22 g. While this is slightly more, my guess is that is not statistically signficant, and would be chalked up to any user bias or error. Heat treated whole wheat flour may absorb slightly more water, but a larger sample would be needed to know for sure.

3a. Vital Wheat Gluten (Not Heat Treated)

Vital Wheat Gluten is the anti-Celiac flour; it's entirely gluten. It's low in carbs and high in protein (remember gluten is a protein). I typically add a little bit into my whole wheat bread loves, as whole wheat flour contains less gluten than white flour, so it has a harder time rising and can become dense without a little extra gluten.

I'm predicting that not only will this not need very much water, but that it won't really come together at all, and would be very stringy and tough. Gluten is what gives bread structure, but too much would be gummy and gross (my prediction, let's see how it turns out).

Surprisingly, the VWG was able to hold together into a dough without being too difficult to combine. The 30 g of vital wheat gluten needed about 25 g of water, which is a little more than even the whole wheat flour. Note that biting into this is like chewing on rubber; I would not recommend a 1:1 swap of any flour to vital wheat gluten pretty much anywhere.

3b. Vital Wheat Gluten (Heat Treated)

This is the final flour that cannot be consumed raw. Heat treating can also be done by microwaving in 30 second intervals.

Interestingly, I noticed that vital wheat gluten seemed to brown quite a bit more in the oven as compared to the white flour or whole wheat. It also took more water than the original VWG as expected - about 31 g for 30 g flour. This was the first one to have more water than flour now.

4a. Oat Flour

Oat flour is a very common healthy flour substitute that myself and others tend to use. It's cheap (if you make it yourself by grinding up quick or rolled oats), high in fiber, can be eaten raw, and gluten free. My oat flour here is just store brand quick oats that I blended myself in my food processor, which may be not as fine as storebought oat flour.

Oats also tend to soak up a lot of moisture, especially if you let the dough chill in the fridge for a little bit after mixing it. Meaning, you may want to keep the dough slightly sticky, as it'll absorb more water while it chills. My assumption here is that it will need a bit more water than the whole wheat flour though.

Turns out, 30 g of oat flour needed exactly as much water as whole wheat flour, 22 g. I left the dough slightly sticky though, as more water will be absorbed by the oats while it chills. The flour mixed well with the water to form the dough, and it instantly smelled like bland oats as soon as you started adding the water.

4b. Quick Oats

Since oat flour is just ground up oats, I wanted to see if using whole quick oats would yield different results. I don't have any rolled oats on hand, but I would assume that these would yield similar results.

The whole quick oats ended up taking in less water than the oat flour, only 20 g for the 30 g of quick oats. My guess here is that with less surface area, since the oats are not ground up, the oatmeal wasn't able to bind to as much water. Like with the oat flour above, it was left slightly sticky to give room for delayed water absorption.

5. Cornstarch

Cornstarch is almost never used as the sole flour in a recipe (except in sequilhos). Rather, I typically see a little bit used when oat flour is the main flour in a recipe, in order to help with the texture and replicate the feeling of a flour with gluten, while still being gluten free.

Typically, cornstarch is used more in cooking than baking. It, along with flour, are typically used to thicken a sauce in a dish. A common conversion is 1 tbsp cornstarch for every 2 tbsp all purpose flour, so it would be interesting to see if that holds up here.

This was a super weird one to make. I don't think I've ever see anything be so dry and so wet at the same time; I didn't think that was possible. I ended up with about 26 g of water for 30 g of cornstarch, but I originally overshot the water, and had to double everything to compensate.

As soon as you start mixing in water, it gets super clumpy and hard to mix; you need to use your hand. But then almost instantly, you end up with a putty or glue. This felt like an elementary school science experiment. I was able to clump everything together in my hand to form a reasonable dough ball, but as soon as I put in back in the bowl it turned to a pastey liquid.

Turns out that I accidentally created Oobleck lmao. This was fun to play with, but not to eat. Into the garbage it went.

6. Cocoa Powder

While not a flour, cocoa powder is a powdered solid ingredient that can certainly act as a flour in small amounts. Look at brownies; about the same weight of flour and cocoa powder can be used in a recipe. Knowing the conversion ratio here should be helpful in swapping out all purpose or oat flour in place of cocoa powder for a chocolate flavor.

I won't be testing cacao or carob powders here, but I would assume that these would yield similar results. Also, I only have Dutch process cocoa on hand, but I would assume that natural cocoa would also be similar.

I knew that cocoa needed a bit of water and stirring to get it fully hydrated, but I didn't expect it to be this much. 40 g of water for 30 g of cocoa powder is the highest amount of water so far. At first, the water doesn't look like it's doing too much other than making the color a little brighter. But as you add more water and stir, you all of a sudden get a dark brownie colored ball with an intense chocolate smell.

7a. Whey Protein Powder

Whey protein is the more common type of protein powder as compared to casein. It's known for not binding to water very well, which is why it works so well in a protein shake. It's basically the opposite as casein in terms of using as a flour. A common question in many protein powder recipes is if you can substitute casein for whey, and the answer is almost always a no, which I hope to show below.

The 30 g of whey protein only needed 14 g of water, and even then it was still a bit sticky. This is by far the lowest on the list so far, and I'm predicting that it will stay that way. Add too much water and whey can easily mix in cohesively to the liquid, making very poor as a solid flour replacement, but great for dissolving into something.

7b. Casein Protein Powder

Casein protein is the lesser known milk protein, with the other being whey. It acts more like a flour, holding on to water very well, which is why it would be a good ingredient in a cookie dough, and a bad ingredient in a protein shake (it would clump up). Casein absorbs a lot of liquid; my estimate is that it will fall somewhere between oat flour and coconut flour.

As I predicted, casein and whey are basically opposites. For 30 g of casein protein, 70 g of water was needed. That's 5 times the amount of water as the whey, with the 2 protein powders currently being the most and least absorbent tested so far.

The next time you try to replace casein with whey (or vice versa), keep this in mind. Use casein to thicken and make something more solid, and use whey to add more protein without changing the consistency too much.

8. Coconut Flour

Coconut flour is another gluten free flour alternative. It's made from dried and defatted coconuts, similar to how peanut flour (PB2 or PBFit) is made. It's low in fat and carbs and high in fiber, as well as having a slightly sweet taste.

Coconut flour is also widely known for absorbing a ton of liquid. I've heard estimates that replacing that using 1/4 cup of coconut flour is equivalent to 1 cup of all purpose flour, meaning it would absorb 4 times as much liquid.

Coconut flour is insane; I don't know how it could hold on to water so well. It took 120 g. of water for just 30 g of coconut flour. That's 4 times the amount of water by weight than coconut flour. As such, the dough ball was easily the biggest that was tested. Recall that the AP flour needed only 17 g of water, which is 7 times less than the coconut flour. I suppose that using 1/4 of coconut flour for every cup of standard flour isn't as ridiculous as it sounds.

9. Chia Seeds

Similar to flax seeds, chia seeds are also very high in Omega-3s and fiber. There is a strong difference in texture though; chia seeds are normally consumed whole, whereas flax seeds tend to be ground into a flour. You could blend the chia seeds, but here I'll be using whole chia seeds.

It should be noted that chia seeds swell up with water, which is what thickens overnight oats. This can take a little bit though, so while the dough will at first look too wet, you'll need to undershoot the water a bit to end up at the consistency you desire. Oat flour is similar in this regard, but chia seeds are a much more extreme version of the same concept.

Whole chia seeds was admittedly a weird test; moreso to see just how chia seeds absorb water. I added 30 g of water to 30 g of chia seeds in a bowl and stirred. It looked way too liquidy at first; but after 5 minutes, I had a solid ball of dough that I could handle and roll.

A typical chia egg is a 3:1 water to chia seed ratio by weight, whereas this was a 1:1 ratio. I basically made a dry chia egg, and showed why you need to let it sit for a few minutes (for the chia seeds to gel) before adding to a recipe as an egg substitute.

This little ball also has 10 g of fiber. The majority of American's aren't consuming enough fiber; the RDA for men and women respectively are 38 g and 25 g, but the average American adult only consumes 10-15 g of fiber daily. I'm not saying eat chia dough balls, but maybe try adding chia seeds into your diet.

10. Peanut Flour

Peanut flour, similar to coconut flour, is made by defatting and drying peanuts, and grinding them into a flour, leading to a product that's fairly low in carbs and fat, but high in protein (basically a vegan protein powder).

It's typically known by the brand names PB2 or PBFit, which are versions of peanut flour with a little bit of salt and sugar added to it. The brand I'm testing today is the Walmart GV Powdered Peanut Butter. My assumption is that it will absorb quite a bit of water, but not nearly as much as the coconut flour.

This one surprised me a bit. For some reason, I expected peanut flour to be able to hold on to a lot of water, similar to the cocoa powder, but it was a bit less. The 30 g of peanut flour only needed about 29 g of water to make it into a dough

11. Flaxmeal

Flaxmeal, also known as ground flaxseed or flaxseed meal, is made by grinding together whole flaxseeds until a flour is formed. It's high very high in Omega-3 fatty acids as well as fiber, while being low in carbs and gluten free.

Typically not used on its own, flax is usually added as an additional flour in small amounts in keto or GF recipes; however, I wanted to isolate it here and test how it would be as the sole flour.

For some reason, I expected ground flax to have results closer to chia seeds. But it definitely took in less water; only about 21 g of water for 30 g ground flaxseed. It had a cookie dough like texture, but certainly hardened in the fridge. It turned into something you could crumble (which I did over a bowl of yogurt lol)

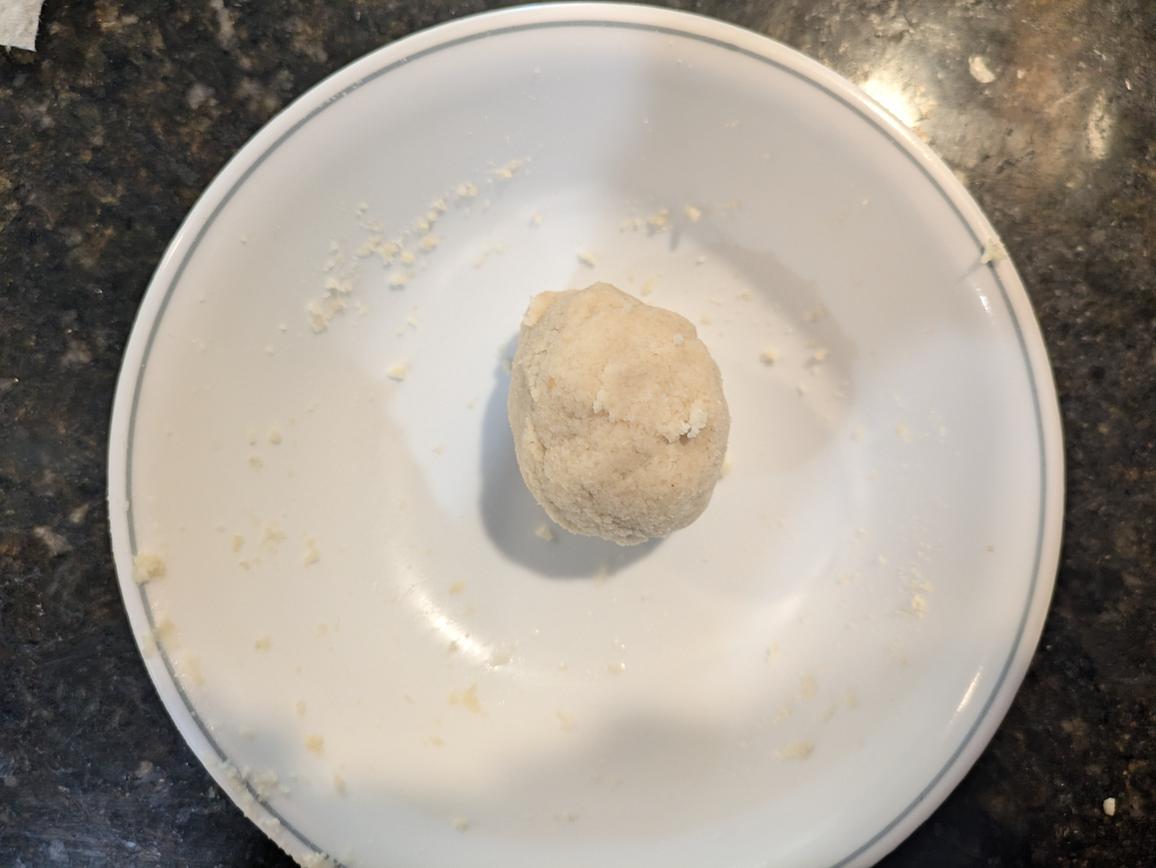

12a. Almond Flour

Almond flour is one of the most common grain free keto flours I see used in recipes. It's highly nutritious, but I tend not to use it as it's faily expensive. Almond flour is made by blending blanched almonds (almonds with the skin removed) in a food processor until very fine. I'm assuming that almond flour won't be able to absorb quite as much as peanut flour, but about as much as the oats.

This one surprised me. For some reason, I expected almond to take in more water than the wheat-based flours. In fact, it was nearly the same. The 30 g serving of almond flour needed about 17 g of water to come to a similar consistency as all the rest.

12b. Almond Meal

The only difference between almond meal and almond flour is that almond meal includes the almond skins; it doesn't use blanched almonds. Almond meal can be purchased in a bag, but it is very easy and often cheaper to make your own almond meal by just blending whole almonds.

Almond meal is coarser due to the skins, and is more like finely chopped nuts than a flour. I'm thinking this test should yield similar results to oat flour vs quick oats; comparing a more finely ground flour to a coarser solid.

Almond meal was a weird one. To 30 g of almond meal I added 20 g of water and mixed. It was simultaneously too dry to come together and too wet where water was seeping out of it. I did grind up my own almond meal, so maybe the issue was that it wasn't fine enough? Either way, almond meal cannot be a flour substitute like almond flour can.

13. Millet Flour

Millet is a type of grain that is gluten free, making it a great GF flour alternative to those with celiac disease. Millet can also be eaten raw, making it great for no bake recipes as well. It looks, smells, and feels similar to all-purpose flour, but with a slight yellow-ish hue. I expect it to have an absorption of about the same as white or whole wheat flour.

This aligned with my expections; 20 g of water was added to the 30 g of millet flour in order to become a workable dough. Being a gluten free grain, I would assume this means that you can probably replace all purpose flour for millet flour in a 1:1 ratio in any baked goods and likely be okay.

14. Hemp Seeds

Hemp seeds are a kind of coarse seed that is not ground, similar to chia seeds or whole flax seeds. It has a similar texture to almond meal, if not even more coarse. While chia and flax seeds are known for absorbing a lot of water (think a chia egg or flax egg), I've never heard of a hemp egg. I'm assuming this won't go well.

As predicted, yeah that didn't work; 15 g of water was added to the 30 g of hemp seeds to attemp to make a dough. Just like with almond meal, this didn't come together at all; the "flour" was too course to bind to the water, and instead became a wet sticky mess, no matter how little or much water I added.

15. Psyllium Husks

I'm very interested to see what happens here with the psyllium husks. Psyllium husk is a type of soluble fiber that's used a lot in gluten free bread making to mimic the feel of gluten. Typically, it will be mixed with water and left to rest for a few minutes to gel before adding into the dough, like in my Gluten Free Millet Bread. Since it's known for hydrating and gelling up, I'm predicting this will take a lot of water.

As assumed, the psyllium husk was able to absorb a lot of water; 2.5x its weight. For 30 g of psyllium husk, I was able to mix in 75 g of water in order to become a workable dough. Not quite as much as coconut flour, but it edges out casein protein powder for the silver medal. Not that I'd ever use psyllium husk as a flour; you'd probably be making a beeline to the bathroom if you did.

16. Ground Coffee

Using (decaf) ground coffee, I'm going to attemp a coffee ball. I'm guessing this will fail, as I've seen leftover wet coffee grinds in the garbage can before, and would assume that this would not be able to bind together like the others on this list.

For 30 g of ground coffee, I added 15 g of water and stirred. This felt like holding wet pebbles. There's no way to get this to come together as a cookie dough texture. The texture is very coarse, and the mix feels too dry to stick, but too wet where it's sticky, somehow. Weird.

17. Granulated Sugar

Finally, sugar. This is a stupid one, I know. Sugar is known for dissolving in water, not binding to water like flour does. But I was curious and figured what the heck.

I only added 5 g of water to 30 g of sugar to end up with this wet mess. I basically started to make sugar syrup in a bowl without heating it up. Which I attempted to do; turns out you can caramelize this small amount of sugar just by microwaving for about 45 seconds. Imagine the lazy creme brulee you can make knowing this.

Results

Below is a table of the results, with the grams of water needed to form a dough ball for 30 g of each of the flours tested above.

| Flour Name | Grams of Flour | Grams of Water |

|---|---|---|

| All Purpose Flour (Not Heat Treated) | 30 g | 17 g |

| All Purpose Flour (Heat Treated) | 30 g | 20 g |

| Whole Wheat Flour (Not Heat Treated) | 30 g | 22 g |

| Whole Wheat Flour (Heat Treated) | 30 g | 23 g |

| Vital Wheat Gluten (Not Heat Treated) | 30 g | 25 g |

| Vital Wheat Gluten (Heat Treated) | 30 g | 31 g |

| Oat Flour | 30 g | 22 g |

| Quick Oats | 30 g | 20 g |

| Cornstarch | 30 g | 26 g |

| Cocoa Powder | 30 g | 40 g |

| Whey Protein Powder | 30 g | 14 g |

| Casein Protein Powder | 30 g | 70 g |

| Coconut Flour | 30 g | 120 g |

| Chia Seeds | 30 g | 30 g |

| Peanut Flour | 30 g | 29 g |

| Ground Flaxseed | 30 g | 21 g |

| Almond Flour | 30 g | 17 g |

| Almond Meal | 30 g | 20 g |

| Millet Flour | 30 g | 20 g |

| Hemp Seeds | 30 g | 15 g |

| Psyllium Husks | 30 g | 75 g |

| Ground Coffee | 30 g | 15 g |

| Granulated Sugar | 30 g | 5 g |

| Flour Name | Grams of Flour | Grams of Water |

|---|---|---|

| All Purpose Flour (Not Heat Treated) | 53 g | 30 g |

| All Purpose Flour (Heat Treated) | 45 g | 30 g |

| Whole Wheat Flour (Not Heat Treated) | 41 g | 30 g |

| Whole Wheat Flour (Heat Treated) | 40 g | 30 g |

| Vital Wheat Gluten (Not Heat Treated) | 36 g | 30 g |

| Vital Wheat Gluten (Heat Treated) | 29 g | 30 g |

| Oat Flour | 41 g | 30 g |

| Quick Oats | 45 g | 30 g |

| Cornstarch | 35 g | 30 g |

| Cocoa Powder | 23 g | 30 g |

| Whey Protein Powder | 64 g | 30 g |

| Casein Protein Powder | 13 g | 30 g |

| Coconut Flour | 8 g | 30 g |

| Chia Seeds | 30 g | 30 g |

| Peanut Flour | 31 g | 30 g |

| Ground Flaxseed | 43 g | 30 g |

| Almond Flour | 53 g | 30 g |

| Almond Meal | 45 g | 30 g |

| Millet Flour | 45 g | 30 g |

| Hemp Seeds | 60 g | 30 g |

| Psyllium Husk | 12 g | 30 g |

| Ground Coffee | 60 g | 30 g |

| Granulated Sugar | 180 g | 30 g |

Conclusion

From the tables above, you can get an an estimate of how to replace one type of flour with another in a recipe. I was most interested in the coconut flour, which is able to absorp so much water. I can get a bag for only $4 a pound, and since you need so little, I've found that coconut flour is actually a great cheap GF flour replacement. Typically I see almond flour being used, but coconut is just so much cheaper.

Another great cheap alternative is oat flour, which is probably cheaper than coconut, and also much more versatile. I use either oat flour or quick oats all the time; that's only about $4 for a 42oz canister of oats. Oats are rich in fiber, provide a great nutty taste, and can hold onto a bit of moisture.

Finally, I hope I've demonstrated the difference between whey and casein protein powders, and why you simply can't just sub one for another in a recipe. If you are looking to add protein to something, start with a 50/50 blend of whey/casein, and go from there. Whey can help a cake rise, but it will dry it out. Casein, on the other hand, will keep it moist, but might make it dense. This is why a blend is normally a safe bet.

I've a Python script where you can enter the flours you are converting from and to, along with the amount of the original, in order to find an approximate amount to use. Click here to download the file to run it yourself.

Now if you'll excuse me, I'm about to blend all these dough balls together to create some weird Frankenstein cookie dough.

Ingredients

- 1.33 cup (320 g) Water

- 1/3 cup (30 g) Oat flour

- 6 tbsp (30 g) Quick oats

- 6 tbsp (30 g) Cocoa powder

- 1 scoop (30 g) Whey protein powder, unflavored

- 1 scoop (30 g) Casein protein powder, unflavored

- 1/4 cup (30 g) Coconut flour

- 2.5 tbsp (30 g) Chia seeds

- 1/3 cup (107 g) Sugar free syrup

- Large pinch (0.75 g) Salt

- 1 tsp (3 g) Cinnamon

- 1/2 tsp (2.5 g) Almond extract

- 6 tbsp (90 g) Plain nonfat greek yogurt

- 2 tbsp (32 g) Walnut butter

Epilogue

So cookie dough didn't end up happening...it was too liquidy. So instead, I made it into a chocolate spread. It's surprisingly delicious and high in protein, like a high protein and low sugar/fat nutella.

I just blended together all the dough balls with some sugar free syrup, a pinch of salt, cinnamon, almond extract, nut butter, and greek yogurt

It's a really good spread on toast or in oats that I'd honestly consider making again lol. Each serving is about 2 tbsp or 32 g.

Nutrition Facts

------------------------------------------

Servings: 23

Calories: 47

------------------------------------------

Total Fat: 2.0g (3 %)

Sodium: 21mg (1 %)

Total Carbohydrate: 6.9g (2 %)

Fiber: 1.8g (6 %)

Total Sugar: 0.5g

Protein: 3.7g (7 %)

Total Fat: 2.0g (3 %)

Sodium: 21mg (1 %)

Total Carbohydrate: 6.9g (2 %)

Fiber: 1.8g (6 %)

Total Sugar: 0.5g

Protein: 3.7g (7 %)

Sources

1. How to substitute whole wheat for white flour in baking

2. Vital Wheat Gluten

3. Quaker Oat Flour 101

4. What's the maximum amount of water that oats can absorb?

5. How to Use Flour or Cornstarch to Thicken Sauce, Gravy, and Soup

6. Effect of whey and casein protein hydrolysates on rheological, textural and sensory properties of cookies

7. Everything You Need To Know About Baking With Coconut Flour

8. How to Use Almond Flour As a Replacement

9. Almond Meal vs. Almond Flour. What's the Difference?

10. How To Use Protein Powder CORRECTLY (Whey vs. Casein)

11. How To Make Oobleck